Book review: Hitler's Shadow

Mykola Lebed, Ukrainian secret services architect and main CIA ally in the cold war - the Vatican - the unpredictable Bandera - MI6 versus the CIA in Ukraine - Cold War deep artworld psyops

While researching the topic of CIA links with post-soviet Ukrainian secret services and rightwing nationalists, I came upon the short book Hitler’s Shadow: Nazi War Criminals, U.S. Intelligence, and the Cold War, which relies almost exclusively on declassified CIA and US military documents. It can be read online here.

While there is plenty of fascinating material in the book about the post-war careers of high-ranking German Nazis in both the anti-western Arab world (where their murky careers were often cut short by the local Mukhabarat) and West Germany (where they had fruitful careers helping in the struggle against communism), I will be focusing on the last chapter, ‘Collaborators: Allied Intelligence and the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists’.

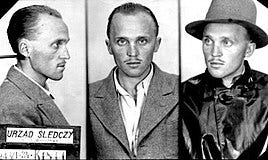

The emergence of Mykola Lebed, father of the SBU (1941-4)

The main character I was interested by is Mykola Lebed’. Lebed created the SBU - Sluzhba Bespeky Ukrainy/Security Services of Ukraine - in 1941.

After the Germans invaded the USSR on June 22, 1941, Bandera’s teams moved into East Galicia. On reaching the East Galician capital city of Lwów on June 30, 1941, his closest deputy Jaroslav Stetsko proclaimed a “sovereign and united” Ukrainian state in the name of Bandera and the OUN/B. Stetsko was to be the new prime minister and Lebed, having trained at a Gestapo center in Zakopane, the new minister for security.

I already wrote about him a bit in a recent article. There are good reasons to return to the story of Lebed’. The same article of mine also treated Valentyn Nalyvaichenko, head of the SBU under Yuschenko and (literal) Godfather of the far right. In a 2015 interview (his political weight had naturally grown after 2014), he stated:

"For the SBU, there's no need to invent anything extra; it's important to base our traditions and approaches on the work of the Security Service of the OUN-UPA from the 1930s to the 1950s,… [The SBU in that period] worked against the aggressor under the conditions of temporary occupation of the territory, had a patriotic upbringing, conducted counterintelligence operations, and relied on the peaceful Ukrainian population, enjoying its unprecedented support. When I was still in the opposition, we thoroughly studied these traditions and the traditions of Lebed and Arsenych-Berezovsky, who created and led the Security Service of the OUN."

Lebed’ employed quite specific ‘traditions’ in the turbulent years of World War Two:

When the war turned against the Germans in early 1943, leaders of Bandera’s group believed that the Soviets and Germans would exhaust each other, leaving an independent Ukraine as in 1918. Lebed proposed in April to “cleanse the entire revolutionary territory of the Polish population,” so that a resurgent Polish state would not claim the region as in 1918. Ukrainians serving as auxiliary policemen for the Germans now joined the Ukrainian Insurgent Army (UPA). Maltz recorded that “Bandera men … are not discriminating bout who they kill; they are gunning down the populations of entire villages.… Since there are hardly any Jews left to kill, the Bandera gangs have turned on the Poles. They are literally hacking Poles to pieces. Every day … you can see the bodies of Poles, with wires around their necks, floating down the river Bug.” On a single day, July 11, 1943, the UPA attacked some 80 localities killing perhaps 10,000 Poles.

Interestingly, the wartime SBU’s methods were actually too extreme for the Germans:

As the Red Army moved into western Ukraine (it liberated Lwów in July 1944) the UPA resisted the Soviet advance with full-scale guerrilla war. Maltz noted that, “Most of the Bandera gangs, men and women, from the villages … are still hiding out in the woods, armed to the teeth, and hold up Soviet soldiers. The Soviets may be the rulers of the towns, but the Bandera gangs reign supreme in the surrounding countryside, especially at night. The Russians…have their hands full…. Hardly a day passes without a Soviet official being killed….”19 The Banderists and UPA also resumed cooperation with the Germans. Though the SD was pleased with the intelligence received from the UPA on the Soviets, the Wehrmacht viewed Banderist terror against Polish civilians as counterproductive.

Go West My Son: help from the Vatican (1944)

The Ukrainian nationalists, who were themselves highly supported by the west Ukrainian Greek Catholic Clergy (Bandera’s own father was a priest in the church), also found it important to reach out to Rome. Lebed’, the spymaster, was also always the one positioned to reach out to foreign governments:

In July 1944, before the Soviets took Lwów, the UHVR (Supreme Ukrainian Liberation Council, established by Stepan Bandera’s nationalists in 1944 as a front to appeal to the western governments) sent a delegation of its senior officials to establish contact with the Vatican and Western governments. The delegation was known as the Foreign Representation of the Supreme Ukrainian Liberation Council (ZP/UHVR). It included Father Ivan Hrinioch as president of the ZP/UHVR; Mykola Lebed as its Foreign Minister; and Yuri Lopatinski as the UPA delegate.

Those better-versed in parapolitics would be able to add something relevant here about the role of the Church here. While Opus Dei was busy in Chile in the years leading up to and under Pinochet, the Catholic Church was also quite active in the eastern, Ukrainian vector.

Bandera splits from Lebed, CIA moves away from the unpredictable Bandera (1948-1959).

In 1948, Lebed’ and Hrinioch split away from Bandera and Stetsko. While Bandera’s group supposedly had the support of 80% of the party, Lebed’ would gain control over access to CIA support.

The UHVR later rejected “attempts by western Ukrainian chauvinists, including Stephen Bandera, to erect a Ukrainian state on a narrowly religious, mono-party, totalitarian basis, since the Eastern Ukrainian nationalists find such a political philosophy unacceptable.” A feud erupted in 1947 between Bandera and Stetsko on the one hand, and Hrinioch and Lebed on the other. Bandera and Stetsko insisted on an independent Ukraine under a single party led by one man, Bandera. Hrynioch and Lebed declared that the people in the homeland, not Bandera, created the UHVR, and that they would never accept Bandera as dictator.

Bandera would grow more and more volatile, uncontrollable, while Lebed embraced his role as a smooth operator for western intelligence services, despite his own relative unpopularity in Ukrainian nationalist circles:

By August 1947 Banderists were represented in every Ukrainian Displaced Person camp in the U.S. zone as well as in the British and French zones. They had a sophisticated courier system reaching into the Ukraine. The CIC (US army Counter-Intelligence Corps) termed Bandera himself, then in Munich, as “extremely dangerous.” He was “constantly en route, frequently in disguise,” with bodyguards ready to “do away with any person who may be dangerous to [Bandera] or his party.

Of course, no matter what differences there might have been between various factions of the Ukrainian nationalists, they found unity on the basis of eurofetishism, denial of any role in the genocides of the 1940s, and continued involvement with German Nazi networks:

Bandera, they never tired of saying, had been arrested by the Nazis and held in Sachsenhausen. Now he and his movement fought “not only for the Ukraine, but also for all of Europe… One [American intelligence] source said in September 1947 that Banderists were recruiting more members in DP camps, their main recruiter being Anton Eichner, a former SS officer…. [In 1947] Lebed sanitized his wartime record and that of the Bandera group and UPA with a 126-page book on the latter which emphasized their fight against the Germans and Soviets.

The book tries to argue that the Americans only protected Bandera with reluctance, but I find that somewhat hard to believe. I am sure he had some convicted lobbyists on his behalf within the American organs as well:

The Soviets learned that Bandera was in the U.S. zone and demanded his arrest. A covert Soviet team even entered the U.S. zone in June 1946 to kidnap Bandera.4The Strategic Services Unit, the postwar successor to the OSS and predecessor to the CIA, did not know about the Soviet team. Nonetheless, they feared the “serious effects on Soviet-American relations likely to ensue from open US connivance in the unhampered continuance of [Bandera’s] anti-Soviet activities on German soil.” Since Bandera himself was not trustworthy, they were just as pleased to get rid of him.

I do find it interesting that Bandera seemed to have been a genuine wild card for the Americans. His secrecy and unpredictability seemed to grow over time. Again, support by the Vatican for Bandera seemed to have played a significant role:

Despite “an extensive and aggressive search” in mid-1947 that included regular weekly updates, CIC officials could not locate Bandera. Few photos of him existed. One CIC agent complained that Bandera’s agents in Germany “have been instructed to disseminate false information concerning the personal description of Bandera.” Bandera’s agents misled CIC as to his location as well. “Aware of our desire to locate Bandera,” read one report, “[they] deliberately attempt to ‘throw us off the track’ by giving out false leads.” CIC suspended the search. Zsolt Aradi, a Hungarian-born journalist with high Vatican contacts and the chief contact at the Vatican for the Strategic Services Unit (SSU), warned that Bandera’s handover to the Soviets would destroy any relationship with the UHVR, which at the time was headed by Banderist members, and with Ukrainian clerics at the Vatican like Buczko, who were sympathetic to Bandera.

The main problem that the Americans had with Bandera seemed to have been his relative independence, as compared to Lebed. I don’t wish to engage in mythology around ‘Bandera the true fighter for Ukrainian independence, who struggled against Russian, German, Polish, and American imperialism’. It seems likelier that he was just too committed to building a fundamentally unstable mafia-fascist parastate, and his personal megalomania came in the way of productive cooperation with the Americans:

“By nature,” read a CIA report, “[Bandera] is a political intransigent of great personal ambition, who [has] since April 1948, opposed all political organizations in the emigration which favor a representative form of government in the Ukraine as opposed to a mono-party, OUN/Bandera regime.” Worse, his intelligence operatives in Germany were dishonest and not secure. Debriefings of couriers from western Ukraine in 1948 confirmed that, “the thinking of Stephan Bandera and his immediate émigré supporters [has] become radically outmoded in the Ukraine.” Bandera was also a convicted assassin. By now, word had reached the CIA of Bandera’s fratricidal struggles with other Ukrainian groups during the war and in the emigration. By 1951 Bandera turned vocally anti-American as well, since the US did not advocate an independent Ukraine.” The CIA had an agent within the Bandera group in 1951 mostly to keep an eye on Bandera.

The Prometheus/Intermarium spy network

Despite Bandera’s obvious status as an uncontrollable contract-killer despot, MI6 was quite interested in him.

British Intelligence (MI6), however, was interested in Bandera. MI6 first contacted Bandera through Gerhard von Mende in April 1948. An ethnic German from Riga, von Mende served in Alfred Rosenberg’s Ostministerium during the war as head of the section for the Caucasus and Turkestan section, recruiting Soviet Muslims from central Asia for use against the USSR. In this capacity he was kept personally informed of UPA actions and capabilities. Nothing came of initial British contacts with Bandera because, as the CIA learned later, “the political, financial, and tech requirements of the [Ukrainians] were higher than the British cared to meet.” But by 1949 MI6 began helping Bandera send his own agents into western Ukraine via airdrop. In 1950 MI6 began training these agents on the expectation that they could provide intelligence from western Ukraine. CIA and State Department officials flatly opposed the use of Bandera. By 1950 the CIA was working with the Hrinioch-Lebed group, and had begun to run its own agents into western Ukraine to make contact with the UHVR. Bandera no longer had the UHVR’s support or even that of the OUN party leadership in Ukraine. Bandera’s agents also deliberately worked against Ukrainian agents used by the CIA. In April 1951 CIA officials tried to convince MI6 to pull support from Bandera. MI6 refused. They thought that Bandera could run his agents without British support, and MI6 were “seeking progressively to assume control of Bandera’s lines.” The British also thought that the CIA underestimated Bandera’s importance. “Bandera’s name,” they said, “still carried considerable weight in the Ukraine and … the UPA would look to him first and foremost.”

I bolded the section about Von Mende because of my interest in the Prometheus program and the Intermarium project. Prometheus was a spy network of anti-Russian nationalists created by inter-war Polish leader Jozef Pilsudsky. Intermarium is the idea of an alliance of Romania, Poland, Ukraine, and the Baltic nations on the basis of rightwing nationalism and opposition to both Germany and Russia. Originally, these ideas were supported by the Americans and the French, then they were taken over by the Poles. In the 1920s and 30s, dissatisfaction with Polish colonial rule by Ukrainian nationalists led to their increasing patronage by the increasingly radical German secret services.

In World War Two, there were powerful forces, concentrated in the SS, that advocated support for radical anti-Russian peripheral nationalisms, from Muslim Chechens and Azeris to Ukrainians. However, they were generally overruled by powerful factions in the Wehrmacht, whose need for resources necessitated heavy-handed methods in Ukraine and beyond. On this topic, I recommend Rossolinski-Liebe’s book ‘Stepan Bandera’ and Himka’s ‘Ukrainian Nationalists and the Holocaust’. Nagy-Talavera’s book ‘the Green Shirts and the Others’ is perhaps even better in describing the conflicts between various factions of the Nazi state over support to Romanian and Hungarian fascists.

After the war, this network would be taken over by the Americans. The Anti-Bolshevik Bloc of Nations (itself created in 1943 by Bandera’s OUN) would unite them, under the umbrella of the new transatlantic sponsor.

London more extreme than Washington on the Ukrainian question

The tendency on behalf of the British to support more extreme approaches to fighting the Russians has contemporary echoes. Kit Klarenberg has written about how British Boris Johnson pushed Ukraine towards a more militaristic position in April 2022 than even the Americans desired, blocking attempts by the Ukrainian and Russian governments to come to a peace deal.

https://fxtwitter.com/KitKlarenberg/status/1728410611019596187

https://fxtwitter.com/KitKlarenberg/status/1728411235266244905

Anyway, the CIA were quite displeased with the British infatuation with Bandera. I find it particularly interesting that the Americans admitted that the Soviets had done well in bringing over the younger generation of western Ukrainians onto their side. This stands in stark contrast to the usual line that West Ukrainians were uniformly opposed to Soviet rule, and points to a more nuanced picture of generational and class struggle within West Ukrainian rural society:

But the CIA and State Department officials were “very strongly opposed” to London’s idea of returning Bandera to the Ukraine. Bandera, the Americans said, had “lost touch with feelings in the Ukraine, particularly in the former Polish territories where… the Soviet government had been successful to a remarkable degree in transforming the mentality of the younger generation.” For the CIA, the best solution for intelligence in the Ukraine was the “political neutralization of Bandera as an individual….” The British argued that such “would lead to a drying up of recruits” and “would disrupt British operations…. MI6 disregarded the CIA statement that “Bandera…is politically unacceptable to the US Government.”

Of course, MI6 had no qualms with dealing with Bandera. He was just another brutal bandit. The British organs had dealt with hundreds in the past, and would happily deal with many more in the future.

Bandera was, according to his MI6 handlers, “a professional underground worker with a terrorist background and ruthless notions about the rules of the game…. A bandit type if you like, with a burning patriotism, which provides an ethical background and a justification for his banditry. No better and no worse than others of his kind….”

Despite London’s enthusiasm for banditry, eventually Bandera proved too much, and the Anglo-Saxons found unity in promoting Lebed:

the UHVR rejected Bandera’s authoritarian approach and demanded unity in the emigration. In messages brought from the Ukraine by CIA agents, UHVR insisted in the summer of 1953 that Lebed represented “the entire Ukrainian liberation movement in the homeland.” American and British officials tried to reconcile Bandera to Lebed’s leadership, but Bandera and Stetsko refused. In February 1954 London had enough. “There appeared,” reported Bandera’s handlers, “to be no alternative but to break with Bandera in order to safeguard the healthy ZCh/OUN elements remaining and be able to continue using them operationally…. The break between us was complete.” MI6 dropped all agents-in-training still loyal to Bandera. In July MI6 informed Lebed that it “would not resume [its] relationship with Bandera under any circumstances.” MI6 maintained its four wireless links in Ukraine, now run by a reconstituted ZCh/OUN, and shared intelligence from the links with Lebed and the CIA.

However, Bandera was able to continue on for several years through his trusty contacts with Nazi-era German intelligence (who also supported fascist Russian nationalists), which had also found a second life under American support:

The BND, the West German intelligence service under former Wehrmacht Gen. Reinhard Gehlen, formed a new relationship with Bandera. It was a natural union. During the war, Gehlen’s senior officers argued that the USSR could be broken up if only Germany wooed the various nationalities properly. Bandera had continued lines into the Ukraine, and in March 1956 he offered these in return for money and weapons…. Bandera’s personal contact in West German intelligence was Heinz Danko Herre, Gehlen’s old deputy in Fremde Heere Ost who had worked with the Gen. Andrei Vlassov’s army of Russian émigrés and former prisoners in the last days of the war and was now Gehlen’s closest adviser.

Honestly, it is hard to believe that Bandera was really abandoned by the anglosaxons, when his operations involved so many American and British instruments. I also find it questionable whether Bandera only ‘attempted to penetrate US military and intelligence officers’, or if there was more to it.

Bandera remained in Munich. He had two British-trained radio operators, and he continued to recruit agents on his own. He published a newspaper that spewed anti-American rhetoric and used loyal thugs to attack other Ukrainian émigré newspapers and to terrorize political opponents in the Ukrainian emigration. He attempted to penetrate U.S. military and intelligence offices in Europe and to intimidate Ukrainians working for the United States. He continued to run agents into the Ukraine, financing them with counterfeit U.S. money. By 1957 the CIA and MI6 concluded that all former Bandera agents in Ukraine were under Soviet control. The question was what to do. U.S. and British intelligence officials lamented that “despite our unanimous desire to ‘quiet’ Bandera, precautions must be taken to see that the Soviets are not allowed to kidnap or kill him … under no circumstances must Bandera be allowed to become a martyr.”

In any case, Bandera’s time in Germany saw his continuous mafiazation. Considering that the SBU itself is constantly implicated in petty racketeering affairs, accusing business opponents of SBU patrons of ‘sponsoring terrorism’ in order to take over their businesses (more on this in a later post), it seems like Nalyvaichenko was right in many ways when he said that the SBU aims to continue the traditions of the 1940s.

The Bavarian state government and Munich police wanted to crack down on Bandera’s organization for crimes ranging from counterfeiting to kidnapping.

Unfortunately for Bandera, his attempts to ingratiate himself with the Americans were to prove too potentially successful, with his assassination by the Soviets taking place 10 days after the following visa recommendations by the CIA in Munich:

By September Herre reported that the BND was getting “good [foreign intelligence] reports on the Soviet Ukraine” as a result of their operations.78 He offered to keep CIA fully informed as to Bandera’s activities in return for a favor. Bandera had been trying to obtain a U.S. visa since 1955 in order to meet with Ukrainian supporters in the United States and to meet with State Department and CIA officials. Herre thought that a visa procured with West German help would improve his own relationship with Bandera. CIA officials in Munich actually recommended the visa in October 1959.

The Americans and Lebed

Despite how successful their relationship would become in the future, at first it was marred by difficulties. Once again, representatives of the Vatican tried to smooth over these problems:

Attempts to build a relationship in 1945 and 1946 between the SSU (US Strategic Services Unit, a precursor to the CIA) and the Hrinioch-Lebed group never materialized owing to its initial mistrust. In December 1946 Hrinioch and Lopatinsky asked for U.S. help for operations in the Ukraine ranging from communications to agent training to money and weapons. In return, they would create intelligence networks in the Ukraine. Zsolt Aradi, the SSU’s contact in the Vatican, approved the relationship. He noted that the “UHVR, UPA, and OUN-Bandera are the only large and efficient organizations among Ukrainians,” and that Hrinioch, Lebed and Lopatinsky were “determined and able men… resolved to carry on…with or without us, and if necessary against us.” The SSU declined. A later report blamed the Ukrainians for “ineptitude in arguing their case and factionalism among the emigration.”

Despite his later attempts to whitewash his record, declassified American intelligence reports were quite sanguine about Lebed’s wartime record, not that it affected their willingness to cooperate with him:

A CIC report from July 1947 cited sources that called Lebed a “well-known sadist and collaborator of the Germans.” Regardless, the CIC in Rome took up Lebed’s offer whereby Lebed provided information on Ukrainian émigré groups, Soviet activities in the U.S. zone, and information on the Soviets and Ukrainians more generally.

Increasing cold war tensions intensified American interest in Lebed. They needed a professional covert operative, and the quiet. experienced Lebed fit the bill much better than the explosive Bandera:

The Berlin Blockade in 1948 and the threat of a European war prompted the CIA to scrutinize Soviet émigré groups and the degree to which they could provide crucial intelligence. In Project ICON, the CIA studied 30 groups and recommended operational cooperation with the Hrinioch-Lebed group as the organization best suited for clandestine work. Compared with Bandera, Hrinioch and Lebed represented a moderate, stable, and operationally secure group with the firmest connections to the Ukrainian underground in the USSR. A resistance/intelligence group behind Soviet lines would be useful if war broke out. The CIA provided money, supplies, training, facilities for radio broadcasts, and parachute drops of trained agents to augment slower courier routes through Czechoslovakia used by UPA fighters and messengers.

Lebed goes to New York: the pro-WW3 lobbyist

It was in the New World that Lebed truly came into his own. Nevertheless, old nightmares from the Old World would still haunt him:

Hrinioch stayed in Munich, but Lebed relocated to New York and acquired permanent resident status, then U.S. citizenship. It kept him safe from assassination, allowed him to speak to Ukrainian émigré groups, and permitted him to return to the United States after operational trips to Europe. His identification in New York by other Ukrainians as a leader responsible for “wholesale murders of Ukrainians, Poles and Jewish (sic),” has been discussed elsewhere.

Despite occasional unpleasant brushes with the past, Lebed was cherished by the CIA for his Gestapo-style efficiency:

CIA handlers pointed to his “cunning character,” his “relations with the Gestapo and … Gestapo training,” that the fact that he was “a very ruthless operator.” “Neither party,” said one CIA official while comparing Bandera and Lebed, “is lily-white.”

He was also favored by the CIA because of relative lack of personal ambitions and his high level of covert hygiene, as compared to Bandera:

On the other hand, Lebed had no personal political aspirations. He was unpopular among many Ukrainian émigrés owing to his brutal takeover of the UPA during the war––a takeover that included the assassination of rivals. He was absolutely secure. To prevent Soviet penetration, he allowed no one in his inner circle who arrived in the West after 1945. He was said to have a first-rate operational mind, and by 1948 he was, according to Dulles, “of inestimable value to this Agency and its operations.”

Bandera and Lebed did find common cause, like contemporary Ukrainian nationalists, in castigating the West for not being eager enough to enter nuclear war with their Russian enemy:

Like Bandera, Lebed was also constantly irritated that the United States never promoted the USSR’s fragmentation along national lines; that the United States worked with imperial-minded Russian émigré groups as well as Ukrainian ones; and that the United States later followed a policy of peaceful coexistence with the Soviets.

The following is a quote from Rossolinski-Liebe’s book on Bandera:

In 1958 Bandera still claimed that “The Third World War would shake up the whole structure of world powers even more than the last two wars”. The number of victims that such a war would create did not matter to the Leader, because nationalist independence was more important than human life. Bandera claimed that:

A war between the USSR and other states would certainly cause a great number of victims to the Ukrainian nation, and also probably great destruction of the country. Nevertheless, such a war would be welcomed not only by active fighters-revolutionaries, but also by the whole nation, if it would give some hope of destroying Bolshevik suppression and achieving national independence.

Bandera was against the reduction of nuclear weapons and claimed that the “fear of nuclear war” in the West was groundless. He argued that the West did not understand the true nature of the Soviet Union and was too afraid of a nuclear war. According to him, the politics of appeasement toward the Soviet Union was a mistake. The West should understand that it was threatened by the Soviet Union’s nuclear power and should have demonstrated its own power.

AERODYNAMIC: deep psychological operations against Soviet Ukraine

Though the bloody civil war that the West airlifted military supplies to in Western Ukraine gradually subsided, western intelligence services were heartened by news that anti-Soviet activity could have changed outside of the Western regions:

Washington was especially pleased with the high level of UPA training in the Ukraine and its potential for further guerrilla actions, and with “the extraordinary news that … active resistance to the Soviet regime was spreading steadily eastward, out of the former Polish, Greek Catholic provinces.”

While US cooperation with Lebed’s nationalists began in the heat of armed civil war, it gradually evolved into more of a covert operation:

A resistance/intelligence group behind Soviet lines would be useful if war broke out. The CIA provided money, supplies, training, facilities for radio broadcasts, and parachute drops of trained agents to augment slower courier routes through Czechoslovakia used by UPA fighters and messengers. As Lebed put it later, “the … drop operations were the first real indication … that American Intelligence was willing to give active support to establishing lines of communication into the Ukraine.” CIA operations with these Ukrainians began in 1948 under the cryptonym CARTEL, soon changed to AERODYNAMIC.

AERODYNAMIC began operating more and more on the minds of Soviet Ukraine, rather than simply attempting to defeat the Soviet Union militarily:

Beginning in 1953 AERODYNAMIC began to operate through a Ukrainian study group under Lebed’s leadership in New York under CIA auspices, which collected Ukrainian literature and history and produced Ukrainian nationalist newspapers, bulletins, radio programming, and books for distribution in the Ukraine. In 1956 this group was formally incorporated as the non-profit Prolog Research and Publishing Association. It allowed the CIA to funnel funds as ostensible private donations without taxable footprints.To avoid nosey New York State authorities, the CIA turned Prolog into a for-profit enterprise called Prolog Research Corporation, which ostensibly received private contracts. Under Hrinioch, Prolog maintained a Munich office named the UkrainischeGesellschaft für Auslandsstudien, EV. Most publications were created here. The Hrinioch-Lebed organization still existed, but its activities ran entirely through Prolog.

Through ‘Prolog’, the CIA would be bankrolling art that was not always overtly political, but which aimed to create a separate, non-Soviet Ukrainian subject. The importance of art in CIA psychological operations (or ‘ontological operations’, insofar as they aim at creating an entirely new subjects, rather than simply influencing interpretations of single events) has been profoundly analyzed by Aaron Moulton’s recent essay ‘the Influencing Machine’, which I can’t recommend enough.

Prolog recruited and paid Ukrainian émigré writers who were generally unaware that they worked in a CIA-controlled operation. Only the six top members of the ZP/UHVR were witting agents. Beginning in 1955, leaflets were dropped over the Ukraine by air and radio broadcasts titled Nova Ukraina were aired in Athens for Ukrainian consumption. These activities gave way to systematic mailing campaigns to Ukraine through Ukrainian contacts in Poland and émigré contacts in Argentina, Australia, Canada, Spain, Sweden, and elsewhere. The newspaper Suchasna Ukrainia (Ukraine Today), information bulletins, a Ukrainian language journal for intellectuals called Suchasnist (The Present), and other publications were sent to libraries, cultural institutions, administrative offices and private individuals in Ukraine. These activities encouraged Ukrainian nationalism, strengthened Ukrainian resistance, and provided an alternative to Soviet media.

CIA support to Ukrainian nationalist cultural activities was highly extensive:

In 1957 alone, with CIA support, Prolog broadcast 1,200 radio programs totaling 70 hours per month and distributed 200,000 newspapers and 5,000 pamphlets.

The importance of Ukrainian nationalism as an anti-Soviet weapon was highly appreciated:

One CIA analyst judged that, “some form of nationalist feeling continues to exist [in the Ukraine] and … there is an obligation to support it as a cold war weapon.” The distribution of literature in the Soviet Ukraine continued to the end of the Cold War.

Remarkably, the CIA-sponsored network of Prolog and AERODYNAMIC assets was even successful in entering the Soviet Union itself on a non-covert level. Lebed, the World War Two genocidal butcher, remained the calm manager of this group of ‘well-meaning artists’:

Prolog also garnered intelligence after Soviet travel restrictions eased somewhat in the late 1950s. It supported the travel of émigré Ukrainian students and scholars to academic conferences, international youth festivals, musical and dance performances, the Rome Olympics and the like, where they could speak with residents of the Soviet Ukraine in order to learn about living conditions there as well as the mood of Ukrainians toward the Soviet regime. Prolog’s leaders and agents debriefed travelers on their return and shared information with the CIA. In 1966 alone Prolog personnel had contacts with 227 Soviet citizens. Beginning in 1960 Prolog also employed a CIA-trained Ukrainian spotter named Anatol Kaminsky. He created a net of informants in Europe and the United States made up of Ukrainian émigrés and other Europeans travelling to Ukraine who spoke with Soviet Ukrainians in the USSR or with Soviet Ukrainians travelling in the West. By 1966 Kaminsiky was Prolog’s chief operations officer, while Lebed provided overall management.

Even without Lebed’s direction, Prolog and AERODYNAMIC continued under various names, with a new generation in charge. In what is certainly not an exception, this network created by key executors of the Holocaust eventually found itself closely cooperating with anti-Soviet Zionist Jews:

Lebed retired in 1975 but remained an adviser and consultant to Prolog and the ZP/UHVR. Roman Kupchinsky, a Ukrainian journalist who was a one-year-old when the war ended, became Prolog’s chief in 1978. In the 1980s AERODYNAMIC’s name was changed to QRDYNAMIC and in the 1980s PDDYNAMIC and then QRPLUMB. In 1977 President Carter’s National Security Adviser Zbigniew Brzezinski helped to expand the program owing to what he called its “impressive dividends” and the “impact on specific audiences in the target area.” In the 1980s Prolog expanded its operations to reach other Soviet nationalities, and in a supreme irony, these included dissident Soviet Jews. With the USSR teetering on the brink of collapse in 1990, QRPLUMB was terminated with a final payout of $1.75 million. Prolog could continue its activities, but it was on its own financially.

After a long life of service ‘not only to Ukraine, but also to all of Europe’ [ean Civilization], Lebed was not abandoned by his patrons:

In June 1985 the General Accounting Office mentioned Lebed’s name in a public report on Nazis and collaborators who settled in the United States with help from U.S. intelligence agencies. The Office of Special Investigations (OSI) in the Department of Justice began investigating Lebed that year. The CIA worried that public scrutiny of Lebed would compromise QRPLUMB and that failure to protect Lebed would trigger outrage in the Ukrainian émigré community. It thus shielded Lebed by denying any connection between Lebed and the Nazis and by arguing that he was a Ukrainian freedom fighter.