Glossary:

Trilateral Contact Group (TCG): on the war in Ukraine, a negotiations group involving Russia, Ukraine and the OBSCE set up in 2014.

Minsk agreements: Peace agreements signed in Minsk, Belarus in September 2014 following Ukrainian military defeats by members of the Trilateral Contact Group and by representatives of Donbass separatist leaders (without recognition of their role. Following continued fighting and further Ukrainian defeats, it was revised and signed again in February 2015. The agreements involved political amnesty for Donbass separatists and wide-ranging political, economic, and juridical autonomy for the region, reintegrated inside Ukraine. Minsk did not concern the status Crimea.

UP: Ukrainska Pravda/Ukrainian Truth. Ukraine’s most influential and respected newspaper. Originally founded by Ukrainian journalists with help from USAID in the early 2000s. Bought out by an affiliate of George Soros (‘Dragon Capital’) in 2021.

Serhii Garmash: Ukrainian journalist that works for various liberal publications such as UP, ‘RadioSvoboda’ (the Ukrainian branch of RFE). Also Ukrainian delegate to the Trilateral Contact Group.

Oleksiy Reznikov: currently Ukrainian defence minister. Before 2014, worked as a corporate lawyer in oligarchic property disputes. Appointed head of the Ukrainian delegation to the Trilateral Contact Group by Zelensky in 2019. In 2020-21, served as Deputy Prime Minister, and as Minister for Reintegration of the Temporarily Occupied Territories of Ukraine.

Introduction

In the last article, we introduced the idea that the liberal Ukrainian elite was opposed to the Minsk agreements on Eurocentric grounds. They feared that implementation of Minsk would end Ukraine’s chances of joining the EU and NATO. This article will explore the logic of this argument.

We will see in this article that Ukrainian liberal analysts feared the proletarian character of Donbass, and the resulting tendency of its voters to oppose economic shock liberalization - ‘reforms’, and EU/NATO integration. In a Ukraine already divided and hesitant over its euro-atlantic future, a return of Donbass would have tipped the electoral scales against euro-optimists.

Reintegration of Donbass recognizes the war as a civil war

We mentioned in our previous article Serhii Garmash’s view that Minsk’s danger was in its ‘subjectivization’ of the LNR and DNR.

How did he explain this danger? First of all, recognizing them as sides of the conflict would remove responsibility from Russia, thereby allowing the west to remove sanctions on Russia. One UP article worried that by holding elections per Minsk and integrating the political leaders of the L/DNR into Ukrainian politics, the conflict would simply become an internal one and Ukraine ‘would no longer be able to ask for help from the global community’.

Garmash explained what he meant by the danger of ‘subjectivizing Donbass’:

[The Minsk agreements] Have the aim of simply forcing Ukraine to recognize ORDLO (temporarily occupied territories) as a subject, to get us to start talking with them, and thereby to control Ukraine them, once they receive ‘special status’. Then there will be no possibility of NATO-expansion to the east or Ukraine’s entry to NATO. Because Moscow will block this question through them, just like all the others – integration with the EU, the language question, all our domestic questions.’

Minsk’s recognition of the conflict as an internal one would mean giving a voice to the population of the Donbass. It would no longer be possible to simply slander certain beliefs as ‘fifth columnists expressing Kremlin foreign policy objectives’ – Ukrainians holding such views would be allowed to participate in Ukrainian politics life. Minsk involved the Donbass separatist leaders being amnestied, not arrested or otherwise liquidated as per the Ukrainian government’s numerous ‘de-occupation plans’, such as the 2021 Reznikov Plan. They would create an alternative political pole in parliament and Ukrainian political life, one opposed to euro-atlantic integration.

This subjectification of Donbass was fiercely opposed by Ukrainian political leaders. As the Secretary of the National Security and Defense Council (NSDC), Oleksiy Danilov put it, Ukraine cannot negotiate with Donbass because “there is no such thing as Donbass … it is a definition imposed on us by the Russian Federation.” Danilov himself was a native of Lugansk, with his grandmother remaining in the LNR. Like other pensioners in the L/DNR, since 2017 the Ukrainian government had stopped paying her pensions. A later installation of this series will treat the distaste UP writers had to Minsk’s stipulation that the Ukrainian government had to pay pensions to inhabitants of the L/DNR, even without having militarily ‘de-occupied’ the region.

One 2017 UP article contrasts ‘Ukrainian national interests’ with ‘interests of the local population’ in Donbass. According to the article, the EU and the Minsk agreements were falsely prioritizing peaceful reconciliation by taking into account the latter instead of only the former. This is described as a ‘compromise with Putin’s Russia’.

The fact that Donbass had, throughout Ukraine’s post-soviet history, consistently opposed joining the EU and NATO should not be news to the reader. For instance, a 2012 poll showed that Donbass had the most anti-EU and anti-NATO views. Only 32% supported, or probably supported joining the EU, where the national average was 52%. While (only) 45% of Ukrainians supported or somewhat supported joining NATO, 7% of respondents in Donbass gave the same answer.

A later article will analyze more closely the electoral gerrymandering of Ukraine established by the non-implementation of Minsk, and the danger to euro-integrationists of several million Donbass voters returning to the electoral field. For now it is simply worth noting that the writers of UP had good reason to fear that the return of Donbass would endanger euro-atlantic integration.

Especially given that Donbass wasn’t alone in Ukraine in its anti-euroatlantic views – the same 2012 poll showed that southern and eastern Ukraine had essentially the same views as Donbass on the EU and NATO. On some questions, other regions of Ukraine were even less pro-euroatlantic than Donbass – 64% of southern Ukrainians supporting the creation of a ‘single state’ with Russia and Belarus, as compared to 57% of respondents in Donbass.

In 2017, after the removal of millions of anti-euroatlantic citizens of Donbass and Crimea, and the imposition of a reign of terror against voices of dissent regarding euroatlantic integration, 34% of Ukrainians still opposed joining the EU, and 44% opposed joining NATO. 66% of respondents in Donbass opposed joining the EU, and 81% opposed joining NATO – the highest figure in Ukraine. And the respondents were only from the part of Donbass controlled by Kiev – which excludes the largest cities, Lugansk and Donetsk. The majority of respondents in the Kharkov and Odessa regions were also opposed to joining the EU. The poll, conducted by the liberal ‘Weekly Mirror/Dzerkalo Tizhnya’, introduced these figures by stating that ‘The strategic goal of the Ukrainian state is to acquire membership in the EU and NATO’.

This fear that reintegration of Donbass would democratically block euro-atlantic integration was commonplace in UP and liberal circles. Even according to the instrumentally pro-Minsk (more on which later) Iryna Heraschenko (Poroshenko’s presidential humanitarian envoy to the Minsk talks), Minsk was a ‘compromise’, but Putin wanted Minsk to give Donbass the right to ‘block our path to the EU and NATO’. While she claimed that Ukraine ‘defeated’ Putin in this endeavour, the majority of UP writers disagreed.

UP shared a 2015 Facebook post by Serhii Rakhmanin, one of the top editors of the liberal Ukrainian publication ‘Weekly Mirror/Dzerkalo tizhnya’, as well as former head of the ultra pro-west party ‘Holos’. The post was a reaction to the signature of Minsk, claiming that ‘we have agreed for the continued implementation of the EU association agreement to take into account the opinions of… Russia’.

Pekar on Donbass and civil war

This idea that the Minsk agreements aimed at recognizing the war in Donbass as a civil, internal one, and that this recognition threatened Ukrainian Euro-atlantic integration, was particularly forcefully argued by Valery Pekar’, an economist and constant writer for UP.

According to him, Russia’s aim is ‘not Donbass… but a manageable chaos, a failure of the Ukrainian democratic modernization project (the success of which which raise the question of modernization in Russia), the failure of the European vector’.

The fact that polls showed that most Ukrainians were dissatisfied with Ukraine’s post-2014 liberal, European reforms did not worry Pekar in claiming that Russians were liable to be jealous of Ukraine.

In a 2021 poll, only 22% of Ukrainians said that they would support Euromaidan again, another 19% said they would support euromaidan with some conditions, 15% said they would support opponents of maidan, and 35% said they would support neither side. 45% of Ukrainians said they would prefer to remain geopolitically neutral, and another 14% said they didn’t know what to think about geopolitical neutrality or bloc-status.

In any case, Pekar goes on to say that this fear of a successful, European Ukraine ‘is why Russia has pushed the idea of ‘the civil war’ in Ukraine’. According to Pekar, ‘In terms of Russian strategic goals, it appears highly likely that Donbass will be quite soon returned to Ukraine’. Russia would rather that the conflict be considered a domestic one, with the possibility of a return of Donbass to Ukraine being thereby possible. The rest of his article is dedicated to explaining how the return of Donbass to Ukraine would block Ukraine’s successful European modernization.

Pekar claims that even if Ukraine took control of Donbass following a total retreat of Russian troops and pro-Russian separatists from the region (ie, took control not per Minsk), the results would not be appealing:

Ukraine receives at its full disposal an almost completely destroyed and plundered (and also mined) territory… Poor and embittered people live there who do not understand anything and hate everyone [my emphasis – EIU]. Ukraine, which, in their opinion, started the war. Russia, which abandoned them to their own devices. Europe and America, which became the cause of all this.

Pekar also worries that this situation would benefit Russia, which would receive

the glory of a peacemaker, laurels from the West (which is terribly happy to settle the conflict), immediate lifting of sanctions, influx of foreign investments (after all, the conditions for business in Russia are better than ours, and the size of the markets and the potential of the economy are greater), a triumphant return to the club of great nations

More importantly for our interests, Pekar worries that ‘Ukrainians would feel betrayed by the west, which would initiate a new ‘reset’ of relations with Russia’. As usual, euro-optimists like Pekar fear that a post-minsk world would decrease their relative political strength and popularity.

Pekar also worries about Ukraine’s inability to economically restore Donbass, and the political danger of the resultant mass unemployment in this industrial region. Interestingly, he also predicts that Donbass would become an analogue to Russia’s Kadyrovite Chechnya, where the local elites are able to blackmail the centre to pour budget spending into the region, otherwise a separatist war might re-emerge. This is relevant in the context of a future installation of this series, which discusses the arguments against federalization of Ukraine, arguments which claim that Russia is hypocritically unwilling to do the same domestically.

The next two dangers that Pekar discusses are ‘national reconciliation’ between veterans of the war on the Ukrainian side and ‘the citizens of Donbass – who are they? Collaborators with the occupiers? Unfortunately stupefied people? Separatists?’ Of course, Pekar does not consider the possibility that they are simply representatives of an alternative political vision for the country, which should be respected as such.

He fears the fair elections that would have to be conducted in Donbass, since ‘any attempts at lustration or discrimination [against the political representatives of Donbass] would be immediately blocked by the western countries and international institutions’.

In turn, Russian investments would return or remain in Donbass and Ukraine as a whole, eased by the lack of sanctions. Ukrainian business would return to the Russian market, which it had already known for decades.

One of Pekar’s biggest fears is the voting patterns of Donbass. ‘Add to this the planned presidential and parliamentary elections, in which residents of the liberated territories will vote. Think about who and how they will vote, how political activity will take place there.’

Along with this, ‘Representatives of the old regime will also return: their fortunes will be restored by international courts, and they are not afraid of judgments in Ukraine. With redoubled activity, they will take revenge, which is unacceptable for an active civil society.’

In short, any return of Donbass to Ukraine would be fraught with the danger of the creation of an anti-euroatlantic political centre of gravity.

‘Patriots and "patriots" will shame [Ukraine] for the concessions to the aggressor, the gigantic costs for the reconstruction of Donbas and the binding conditions of international loans, for the influx of Russian money into the economy and Russian agents into politics. Residents of Donbas will shame Ukraine for the war and their suffering, for the lack of care that might meet their high Soviet standards. Political neutrals will shame Ukraine for the economic crisis and rising prices. Everyone will come up with mutually unacceptable and contradictory demands. Radicals will call for immediate action. Populists will promise simple solutions to complex problems.’

In a Ukraine with Donbass reintegrated, the Ukrainian government will be critiqued for its lack of ‘high soviet standards’ of social protection. This is what Pekar calls Russia’s plan to create ‘managed chaos’ which ruins Ukraine’s chances of ‘democratic, European modernization’. He ends the article by excoriating the Ukrainian elite for lacking a clear plan for what to do with Donbass.

The Donbass tumor must be excised from Ukraine’s European body

The natural conclusion of the liberal anti-Minsk position was to remove Donbass from the Ukrainian body politic. Donbass was conceived as a dangerous tumor which had the potential to infect all of Ukraine with its anti-European views. This removal could be done in either two ways – territorially reabsorbed but without political rights, or territorially abandoned.

The idea of calling Donbass a ‘cancerous tumor’ became quite popular in post-2014 Ukraine. I recently translated an article which tracked the use of this phrase by Leonid Kravchuk (Ukraine’s first president), Oleksiy Reznikov (in charge of reintegration of Donbass, now Defence Minister), and Ukraine’s most famous journalist, Dmitry Gordon. Packaged as a ‘quotation’ of a famous (Soviet) Ukrainian writer, the quote in fact did not exist, though the writer referred to also had his fair share of anti-Donbass chauvinism.

In January 2022, Serhii Garmash openly stated that ‘If… there is the question of either implementing the Minsk agreements on Moscow's terms, or really letting Putin recognize these republics and take them for himself, then I would choose the second’. But to his dismay, ‘However, I am sure that Putin will never take Donbass… Because Donbass for him is an instrument of control over Ukraine’. Like Pekar and all the rest, Garmash, despite being Ukraine’s representative to the trilateral contact group on the peaceful resolution of the war in Ukraine, preferred to abandon Donbass than to reintegrate it peacefully.

But ‘excising the Donbass tumor’ as Reznikov and Garmash recommended was quite problematic, since it meant giving up a significant part of Ukrainian territory, a territory for which the Ukrainian army had been fighting and dying for years. However, plenty of nationalists were quite willing to give up Donbass and quit losing Ukraine’s most nationalist sons and daughters in fighting for an anti-Ukrainian territory.

The most nationalistic, anti-Minsk party in parliament at the time, Ukrop, regularly proposed abandoning the uncontrolled regions of Donbass and erecting a wall on the perimeter. The government set about building this wall already in 2014, promising 40,000 jobs through this project.

Nadezhda Savchenko, a Ukrainian nationalist prisoner of war, heroized during her internment in Russia, shocked the liberal-nationalist segment of society when she returned and advocated direct negotiations with the leaders of L/DNR, and giving up control of Crimea permanently in return for receiving Donbass. She was in turn imprisoned by the Ukrainian government.

Clearly, fear of nationalist backlash upon relinquishment of Donbass couldn’t have been the main reason that the Ukrainian government didn’t simply abandon Donbass. There were also economic interests in holding onto it – Donbass was Ukraine’s most industrially important region. There were also more basic state interests – if Donbass was allowed to leave, other regions could also declare their willingness to leave Ukraine.

Symptomatically, UP articles tended to lack any real plan for what to do with Donbass, or castigate Ukrainian society for lacking such a plan, as Pekar did. What they were consistent about, was acknowledging the hostility of the population in Donbass to reintegration within a euro-atlantic Ukraine.

Motyl’s blunt proposition

The argument for abandoning Donbass was most openly advocated by the American-Ukrainian academic Aleksandr Motyl in an interview to the Ukrainian website apostrophe. The interview is titled ‘Ukraine’s survival is only possible without Donbass and Crimea’. According to Motyl, ‘Ukraine should refrain from a military method of resolving the conflict or, at least, from seizing individual regions of Donbass, because there is a risk of a devastating response from Russia’, a ‘full-scale invasion’ in his words, which is ‘equal to suicide’. He claims that ‘Opting out of the EU is nonsense, especially since Putin himself is not against it. Rejecting NATO is correct, because there will be no such thing.’

Motyl argues against reintegrating Donbass for reasons that should be familiar to us. ‘reintegration will instantly bankrupt Ukraine, lead to the end of reforms, movement to the West, to democracy. Therefore, I am convinced that the removal of Donbass is useful for Ukraine, which should develop itself as if there were no Donbass in the country.’

Here there is no reference to malicious Russian FSB agents that would take power following elections in Donbass – the problem is Donbass as a whole, the danger its electorate represents to ‘reforms’, or rather, to economic shock liberalization. As the popular football hooligan (and subsequently also liberal anti-Yanukovych) slogan went - ‘Spasibo zhitelyam donbassa za presidenta pidorasa’ (Thanks residents of Donbass for our faggot president).

According to Motyl, ‘Ukraine has four strategic priorities - survival, strengthening security, reforms and advancement to the West, preservation of democracy. They can be implemented only without Donbass and Crimea’.

However, in case ‘Putin shows readiness to give up ORDLO [the territories of Donbass uncontrolled by Kiev], then Kiev, for the sake of its own self-preservation, should give them a confederal status, almost unambiguous with full sovereignty - let them have their own political system, their own budget, their own taxes, without representation in the Rada. In a word, let them be only formally part of Ukraine and not interfere with Ukraine’.

But overall, he prefers abandoning them. ‘Let Ukraine develop without them, it certainly won't develop with them.’ Many liberals in Ukraine had the same thoughts. But it was easier for Motyl to say it out loud, since he had no political responsibilities and did not live in Ukraine

Motyl’s attitude towards the citizens of Donbass is also worth citing. He does not see any possibility of them becoming ‘true Ukrainians’. ‘- Do you think there is a chance that Ukrainians in the occupied territories will eventually get rid of the illusion that the Russian Federation is concerned with their fate? - Perhaps, but that is not the question. The question is: will they ever become supporters of Ukraine, true citizens of Ukraine? Hardly.’

Gorbach’s fear of non-alignment through the Donbass tumor

Vladimir Gorbach, an influential analyst at the institute of euro-atlantic cooperation, stated in a 2014 interview for Radio ‘Svoboda’ that holding elections before military control over Donbass by the Ukrainian army would result in a ‘tumor on the body of Ukraine, one which Ukraine will constantly try to cure, and Russia will constantly try to irritate’. Gorbach explains that ‘Russian special service agents’ will strengthen work in Donbass in the leadup to elections and will maintain control of the region, thereby influencing Ukrainian politics.

It is worth emphasizing Gorbach’s long history in facilitating EU-Ukraine relations. He is not a marginal nationalist, but a well educated expert who ran for office as part of pro-western parties like ‘Reform and Order’ in the early 2000s, as well as being involved in the protest organization ‘Pora’ of orange revolution (a copy of Gene Sharp’s Serbian ‘Otpor’) fame.

He had also been a member of the civilian expert council of the EU-Ukraine cooperation committee. In a 2018 article, Gorbach decried those political parties in Urkaine which pushed for a geopolitically neutral Ukraine, claiming that ‘proposing to be a non-bloc country is a crime’, and likening it to the ‘soviet communist’ support of the non-aligned movement in the 20th century.

The biological violence of Gorbach’s ‘tumor’ metaphor is striking. While the article mainly refers to the dangers of granting autonomy rights that we discussed in the previous section, the question still arises as to why the Ukrainian citizens of the Donbass would vote for ‘Russian special service agents’. And a ‘tumor’ is hardly an infectious disease, transmitted on by malicious outsiders, but rather the result of cell defects within the sufferer.

A clue to why Gorbach insists on calling a Donbass reintegrated per Minsk a ‘tumor’ can be glimpsed in his anti-nonalignment article. There, he laments the fact that in August 2018, Ukrainian social polls (excluding Crimeans and those living in the L/DNR) found that only 42% wanted to join NATO, and another 35% supported non-alignment. Worst of all, ‘over the past year the amount of NATO supporters has declined by 6%, while the number of supporters of nonalignment has increased by 6%’. I would venture saying that those in post-2014 Ukraine who answer ‘I don’t know’ often do so due to their fear of publicly voicing anti-NATO opinions. As a result, such a poll would show that NATO-supporters were even more of a shrinking minority.

We’ve seen in our first article that the anti-Minsk camp feared the popularity of ‘peace traps’. What’s more, the amount of NATO-supporters in Kyiv-controlled Ukraine was declining. What would happen if the electorate of L/DNR returned into Ukrainian politics? Nothing that could be welcomed by the likes of Gorbach, certainly.

It is hence natural that the region as such became so stigmatized by europhile commentators, with another UP article writing that ‘Donbass is Russia’s instrument for keeping Ukraine in a state of chaos’. The idea that Minsk was a ‘means of Russian control over Ukraine’ was commonplace in UP articles.

Another constant of UP anti-Minsk articles was the fear of allowing famous L/DNR political leaders such as Giwi and Motorola to enter Ukraine’s political system. This radical, anti-euroatlantic political vector would have great potential to gather around it those many Ukrainians who were highly dissatisfied with Ukraine’s post-2014 world of ethnic chauvinism and extreme market liberalism.

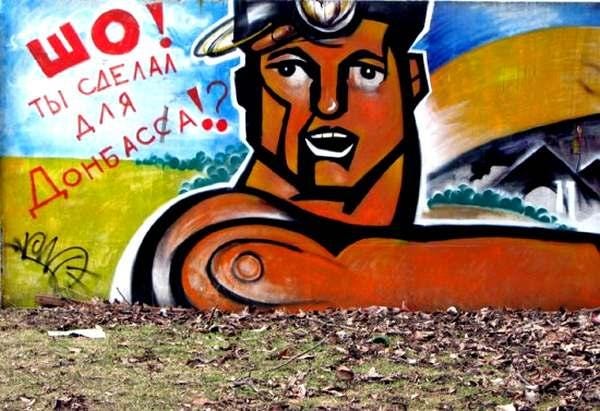

The Donbass proletarian hydra

Another UP article titled ‘Does Minsk have a future’ cited an expert who claimed that were Minsk to be implemented, ‘we will always have to live with a self-resurrecting hydra, appearing on the place of an already defeated enemy’. Fearing the ‘hybrid peace’ of Minsk, which would integrate the enemies of euroatlanticism into Ukraine’s political system, the article recommends instead achieving a ‘real victory’, and goes onto the make the beloved UP arguments for a vague ‘different interpretation’ of the Minsk agreements.

Other UP articles stated the fact of the political unreliability of Donbass citizens even clearer. One article by Volodymyr Dubrovsky openly accepted that ‘our army is perceived there as an enemy, occupation army’. This article also had a political economic aspect – it accepts that the war in Donbass is an ‘internal conflict’, which was ‘created already at the moment of the independence of the former Ukrainian SSR, insofar as the Donetsk proles and elite were, for historical reasons, to a great extent culturally and mentally foreign to the rest of Ukкaine’.

This division between the industrial, proletarian Donbass and the peasant, petit-bourgeois western/central Ukraine was cited by Lenin and Ukrainian Bolsheviks in their justification of why Donbass should be a part of the Ukrainian SSR – that way, the proletarian regions would have a socialist influence on the peasantry, which was otherwise not entirely committed to socialism.

This division between the industrial Donbass and the rest of Ukraine as an explanation for the war in Donbass was also advanced by another pro-maidan Ukrainian website in a 2014 article titled ‘Donbass: the last proletarian revolution in the white world’.

The deindustrializing austerity of EU-integration was less attractive to the industrial workers of the south-east than to western/central lumpenproletarians/semi-peasants whose incomes depended on access to seasonal work in the EU.

Dubrovsky’s article goes on to identify ‘the final choice in favor of the European vector’ (the victory of Euromaidan in February 2014) as the reason for the ‘ignition of this internal conflict’. Thus, even in the pages of UP, there are plenty of voices which clearly identify the war in Donbass as an internal conflict, provoked and continued by the desire of the post-2014 Ukrainian ruling class to prioritize EU-integration – not simply as an invasion by Russia without domestic roots, which is usually how the war is packaged to the west.

While this might seem like the ‘subjectivization of Donbass’ warned against by Garmash, this is false since Dubrovsky’s article strongly argues against implementation of the Minsk Agreements. ‘If we call things by their names, Minsk is hence precisely a capitulation document, signed under Russian tank turrets after Ilovaisk and Debaltsevo’.

Garmash fears Minsk because it would have institutionalized civil difference between euro-optimists and euro-skeptics, not because it would have created this civil difference. It existed anyway, and there was no contradiction between acknowledging the existence of this civil difference and urging against insitutionalizing it.

Dubrovsky’s referendum on euro-atlantic integration and Donbass

Dubrovsky’s article also includes a positive reference towards Valery Pekar’s article ‘Donbas, we kindly ask you to come home’, which we discussed earlier. Dubrovsky agrees with Pekar’s argumentation as to why a return of Donbass to Ukraine on ‘easy conditions’ would be dangerous, due to its potential to reignite the civil conflict between EU-integrators and their opponents.

Dubrovsky’s proposition for how to avoid this civil strife is illuminating. He proposes holding a referendum on whether Ukraine should join the EU or NATO. The referendum would poll the citizens of the L/DNR, by ‘citing Ukraine’s constitutional statements regarding Euroatlantic integration and asking whether they want to be part of Ukraine’. He also proposes polling the citizens of the rest of Ukraine on whether territorial integrity is more important than anything, or if they are fine with the L/DNR remaining outside of Ukraine. He then maps the 4 possible results.

The first option involves the L/DNR voting to re-enter Ukraine, while the rest of Ukraine states that it is tolerant of L/DNR separating from Urkaine. Dubrovsky describes this as a situation in which the citizens of L/DNR ‘consciously decide to become political Ukrainians and move towards Europe, which means there is no longer any conflict.’ A remarkable, if not for how common it has become, identification of Ukrainian nationality with Europhilia.

Since Dubrovsky says that the second and fourth options are derivative of the first and third, I will move onto the third. This option is described as being ‘the most likely’, and it involves ‘a peaceful divorce by mutual agreement’.

The first thing to note about this third option is Dubrovsky’s admission that peace is more popular than territory. It is this unpleasant fact which undergirds much of the fear of the political implications of the Minsk agreements – that peace and economic security will be more popular than militaristic Euroatlanticism. Future installations of this series will examine the fear the UP writers had for the popularity of peace among Ukrainians.

Second, this third option is important in its illustration that conscious expulsion of the Donbass region from Ukraine is the logical endpoint of the anti-minsk position, in its desire to preserve Ukraine’s euroatlantic future. This is true, at least, for perspective which are not focused on political repression of ‘fake Ukrainians’ to overcome civil strife. Future installations will examine proponents of reintegrating Donbass on the basis of the removal of political rights from its citizens.

The article ends with yet another ‘Donbass is a trap’ metaphor. It compares the situation to a ‘freedom-loving wolf with its paw in a trap’. ‘Either it chews off the paw (with blood and pain) and runs to safety (in our case, under the NATO umbrella). Or some, less freedom-loving creations, think ‘what can I do without this paw, it’s mine’ and obediently goes to the slaughter’. Either Ukraine abandons Donbass and joins the Euro-atlantic community, or it keeps Donbass and will never enter the promised land of the EU and NATO.

Conclusion

This installment of my Minsk series has explored the fear held by Ukrainian liberals that Minsk’s reintegration of Donbass would put Ukraine’s euro-integration in danger. They held this to be the case by reference to the anti-EU, anti-NATO sentiments held by most of the several million inhabitants of Donbass.

This installment looked at proposals to simply abandon Donbass – to territorially remove this ‘cancerous tumor’ on the healthy European body of Ukraine. The next installment will look at plans published in UP by quite influential people at the top of the Ukrainian government to return the territory of Donbass, but without political voting rights. But both approaches had the same aims – to safeguard Ukraine’s integration into NATO and the EU.

This is very enlightening. Thank you. In the future, could you explain what "UP" refers to? Also, I hope you'll write one article about, very concretely, who makes up the Ukraine ruling class, which you refer to in this article. A discussion of the structure and membership of the Ukrainian ruling class would give us insight into why this class is so ferociously racist, Russophobic, and against neutrality and exclusively for integration into the EU. Is this a matter of Ukrainian big business leaders and financiers showing class solidarity with the neoliberal EU leadership? Or are the US, UK, etc., deep states putting pressure on the Ukraine ruling class to become the compliant comprador leaders of the post-2014 fake independent state of Ukraine, which is more and more becoming a vassal state of the US that has lost its sovereignty?

My impression after reading this essay is that neo-OUN (neo-Banderite) Ukrainians and Ukrainian liberals both look at Russian-speaking Ukrainians, especially the working-class people of the Donbass, the way many American white people in the post-Civil War south looked at African Americans. The many laws forbidding the expression of Russian, Hungarian, and Roma language and culture are similar to the terrible Jim Crow laws that were passed in the south that turned African Americans into second- or third-class citizens. Why is this not being condemned by the UN? The German Nazis are said to have studied the Jim Crow laws, so I wonder whether the Jim Crow laws are still influential in some circles in Ukraine.

Excellent stuff that explains so much. It's the context and nuance missing from the western propaganda narrative.