Vietnam's lessons for Ukraine

An essay on neutrality, sovereignty, and complicated relationships.

There’s one matter that I don’t write about too often here, though I have plenty of thoughts about it. That topic is the discourse and practice of self-described ‘pro-Ukrainian leftists’. I don’t write about them for several reasons. For one, I knew several of them, and I never find it particularly enjoyable to write about people you know, even if you were never particularly close.

But more importantly, the whole posture comes off as quite ridiculous to me. I never really understood who it was meant to work on – if you’re a pro-American liberal, then sure, ‘support Ukraine’. But if you’re critical of the current world, which leftwing people generally claim to be, I don’t quite understand how one could support a project which calls itself the savior of the ‘rules based’ international order.

Anyway, my surprise is rather misplaced. Plenty of leftwing people are quite happy with the current international state of affairs and want to preserve it – albeit with some improvements for the living standards of citizens of the imperial core. In that case, certainly, it would make sense to support the fight for NATO hegemony.

But things get truly strange when the historical comparisons get let loose.

I haven’t noticed too many comparisons with the invasion of Iraq, which probably makes sense – using such a parallel would imply that Zelensky is just as morally reprehensible as Saddam Hussein is supposed to have been. Instead, the left-liberals have a different beloved historical parallel: Vietnam.

Here is an example of this approach from an archetypal Ukrainian left-liberal writing for Jacobin:

To put it in historical terms, the war in Ukraine is no more a proxy war than the Vietnam War was a proxy war between the United States on one side and the Soviet Union and China on the other. And yet, at the same time, it was also a national liberation war of the Vietnamese people against the United States as well as a civil war between supporters of North and South Vietnam. Almost every war is multilayered; its nature can change during its course. But what does this give us in practical terms?

During the Cold War, internationalists did not need to laud the USSR to support the Vietnamese struggle against the United States. And it is unlikely that any socialists would have advised left-wing dissidents in the Soviet Union to oppose support for the Vietcong. Should Soviet military support for Vietnam have been resisted because the USSR criminally suppressed the Prague Spring of 1968? Why then, when it comes to Western support for Ukraine, are the murderous occupations of Afghanistan and Iraq considered serious counterarguments for aid?

As usual with sophistic arguments, there’s a grain of truth. Indeed, the simple fact of US support for a particular government isn’t enough to decide on the reactionary or progressive essence of that government. Instead, making such a judgment requires some understanding of the nature of that particular government, the domestic interests it represents.

Of course, in reality, the nature of the US government means that it invariably supports reactionary entities.

Regardless, back to the domestic level. There are clearly qualitative differences between how contemporary Ukrainian nationalists and Vietnamese communists – not the ‘Viet Cong’, the derogatory term used by the US invaders – saw their struggle.

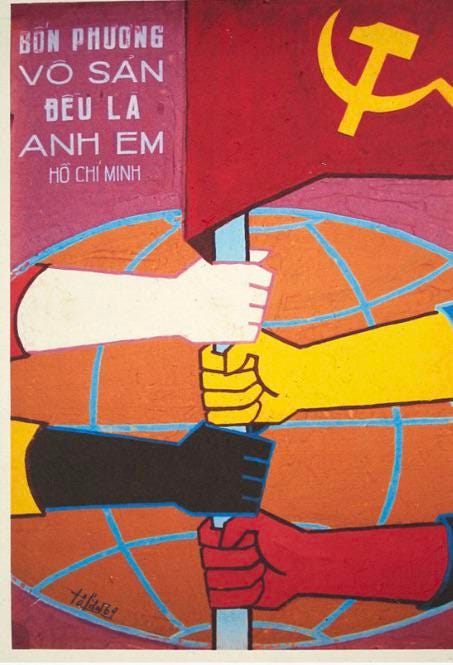

While there are plenty of attempts in western historiography to underplay the role of communist ideology on the Vietnamese, that certainly isn’t how Ho Chi Minh saw it. If you read his works, you can find constant references to and analysis of the works of Marx, Lenin, and Stalin. Today’s Ho Chi Minh museum in Hanoi emphasizes the impact reading Lenin’s theses on the colonial question had on Ho’s political development.

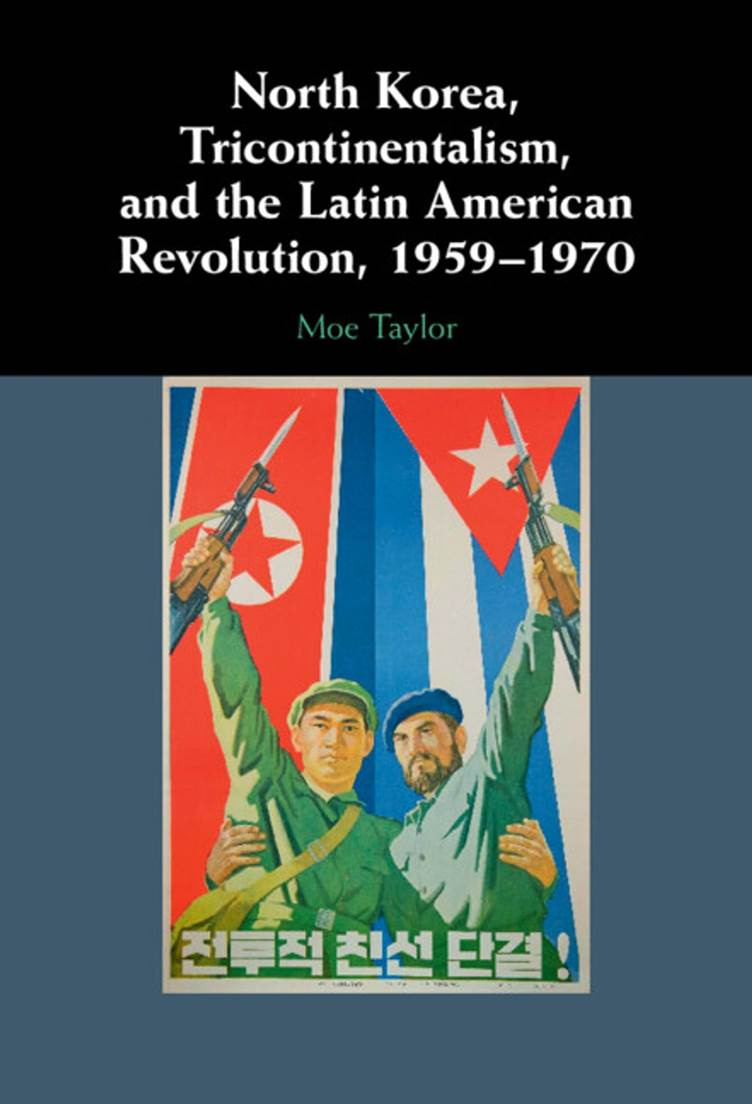

The Vietnamese communists also played a major role in the global third wordlist communist movement known as Tricontentalism, allied in particular with revolutionary Cuba and the DPRK. They had a compelling political line, opposed to both Soviet conservativism and China’s divisive factionalism. Though mainly focused on Cuba and the DPRK, Moe Taylor’s book also has interesting analysis of Vietnam’s role.

While they were certainly fighting for national independence, national liberation in the abstract is quite meaningless. Plenty of Ukrainian nationalists believe that ‘national liberation’ means joining NATO, privatizing the economy, talking only in Ukrainian, and wearing expensive replicas of peasant clothing from 200 years ago.

That is clearly a very different conception of national liberation from the Vietnamese, who focused on economically uplifting the peasantry, industrializing the country, and working alongside the progressive third world to combat western imperialism.

It's also worth mentioning that whenever pro-Zelensky Ukrainian government officials or nationalist media speaks of the Vietnam war, they loudly sympathize with the American puppet regime in the south, as opposed to the ‘barbaric northern communists’. Naturally, the fall of Saigon is often brought up by such figures to urge against ‘betrayal by western allies’.

That’s why it’s rather amusing when Urkainian left-liberals waging English-language info-war patronizingly call on insolent ‘western leftists’ to listen to (their) ‘Ukrainian voice’. But what about the Ukrainian voices in government?

In short, while Vietnam was on the side of the global majority, Ukraine views itself as the vanguard of the ‘civilized west’, fighting a desperate battle against ‘Asiatic orcs’.

But there’s also another contrast between the two – the meaning of sovereignty.

Is a country automatically worthy of ‘support’ if it is fighting a war against a larger neighbor? Few would agree with such a statement, since Nazi Germany, for instance, was much smaller than the USSR it invaded. But what if the larger country is the first to deploy large-scale force?

Beyond the fairly irrelevant, self-obsessed question of who outside observers should ‘support’, what about the country itself – at what point should the imperatives of geographic location take precedence over principled positions? Is it really wise to indefinitely fight a larger neighbor with the support of a distant ally?

The reason I ask these questions is because there is another, much more fruitful way to compare Ukraine to Vietnam, an avenue unexplored by the aforementioned Jacobin article. Both share a complicated, often shared history with a large neighbor. Where Ukraine has Russia, Vietnam has China. But Vietnam chose a far more productive approach towards coexistence.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Events in Ukraine to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.