Translator’s note:

This chapter is from Aglaya Toporova’s 2016 book ‘Ukraine of Three Revolutions’. She was a journalist at ‘Korrespondent Ukraine’ from 1999-2014. Her book is a history of the 2001 ‘Ukraine Without Kuchma’, 2004 ‘Orange’, and 2014 ‘Euromaidan’ ‘revolutions’, which she herself witnessed and reported on. It is also a series of sketches of the cultural and political life that birthed these events.

This chapter is about the infamous figure of the ‘bydlo’ and ‘zhlob’. I chose not to translate these words into English, since the recommended ‘redneck’ is too specifically American and with too many rural overtones. In any case, every English country has its own word for the urban lumpenproletariat – chavs, bogans, and so on.

‘Zhlob’ and ‘bydlo’ are similar to ‘gopnik’, which for whatever reason has become well-known across the world. ‘Bydlo’ was originally used in tsarist Russia to denote a bovine draft animal – an unthinking ox which lives to perform the will of its owner. In modern times, it is generally used by the Russian and Ukrainian liberal opposition, which explains all its political misfortune by reference to the ‘unthinking bydlo mass, who only know how to obey dictators that exploit them, and fear us because it would force them to think for themselves’. Interestingly, the word originally came from the verb ‘to be’ (byt’), and in western slavic language such as Czech, ‘bydlo’ simply means ‘being’, and the Polish ‘bydło’ means ‘home’. ‘Bydlo’ needs a Slavic Holderlin to ruminate upon….

In the Ukrainian language, which has a great deal of influence from western slavic languages, ‘bydlo’ literally means a person who acts as though he were a draught animal. This is close to the word’s slang meaning in Russia and Ukraine today. The modern meaning of ‘bydlo’ is marvelously summed up by the 1988 Soviet film ‘To Kill a Dragon’, where prince Lancelot finds a city (strongly implied to represent the USSR) where the citizens imprison him because they do not want him to kill their beloved dragon-Leader, whose only pursuit in life is to torture his citizens in various creative ways. I recently went to a showing of this film by a local (and well-connected) Navalnist (who wore a big ‘Free Navalny’ t-shirt), who introduced it by telling everyone how Navalny, like the lancelot of the film, went to Russia with the knowledge that the ignorant masses would not support him and allow him to be imprisoned, but went anyway because of his belief in freedom.

I always felt that ‘bydlo’ refers more to the post-Soviet working class, which liberals despise because of its preference for strong leadership that centers preserving employment over ‘liberal experiments’. The word does refer to working animals after all. But ‘zhlob’ is probably closer to the English ‘bum’, more of a lumpenproletariat failure. It is also used to refer to people of any social class who are considered uncultured, dirty, alcoholic, stupid, illiterate, uneducated, rude, or primitive.

The article also briefly refers to the west ukrainian ‘rogul’. This is the word for uneducated and primitive Ukrainian-speaking villagers. It emerged in Austro-Hungarian western Ukraine, which included, for instance, the modern-day Lviv region. It means ‘the one who lives beyond the city gates’, which were called ‘rogatka’. The original image of the ‘rogul’ is accordingly of a group of village lumpens who gather at the city gates in search of work and entry. Some linguists believe that the word came from the word for ‘dark’ – various derivatives of the word for ‘black’ and ‘dark’ and ‘dirt’ were used to refer to the peasant masses in medieval Poland and Russia/Kievan Rus. This, by the way, was part of the basis for the curious racial classism – Sarmatism – of the 18th century Polish landed aristocracy, according to which the nobles belonged to a different race – Iranian Sarmatians – to the Slavic peasants, who had been enslaved many years ago by the Sarmatians. Other linguists believe that ‘rogul’, like ‘bydlo’, also comes from the word for draught oxen.

One more definition – ‘chanson’. A chanson is the genre you will hear play in many post-soviet taxicabs. The english word ‘crooner’ might be similar. In any case, chansons are often about the criminal world, though their singers are not always themselves criminals. The main constant of chansons is their narration of the various problems and passions of the average man of the post-soviet world, surviving between the formal economy and the remnants of the soviet industrial system. This is why they are often identified with the world of ‘bydlo’ and ‘zhlobs’. Mikhail Krug is maybe the most famous chanson singer. Himself not a criminal, he was nevertheless murdered by one in 2002. Below is a music clip of one of his most beloved songs – ‘Kolshik’ or ‘tattooer’. It is worth watching also for the prison audience, which is as good a representation of the image of ‘bydlo/zhloby’ as any. The song starts from 2:30, and the lyrics can be found here.

And P.P.S. – the figure of Viktor Yanukovych was an endless target for the labelling of ‘zhlob/bydlo’. As well as all the population of eastern Ukraine, and, ultimately, all working class (or otherwise) people who opposed ‘enlightened liberal reforms’, or economic shock therapy. This dehumanization has only intensified nowadays, as anyone ‘fortunate’ enough to have encountered the term ‘orc’ or ‘vatnik’ on twitter will know. The Ukrainization of global political discourse continues, which is why I wanted to translate this.

The problem of "bydlos" and "zhlobs" for many years was, perhaps, the main ideological problem in Ukraine. Considering that social, political and economic thought in Ukraine was practically absent, at least not represented in any way in popular and significant media, the main source of inspiration for the local intelligentsia was the endless search for the exact definition of the words "bydlo" and "zhlob" and, accordingly, the search for bydlo and zhlobs among their friends and strangers. The researchers themselves, of course, considered themselves to be part of a certain intellectual, spiritual, even consumer elite. The division of citizens into what one might call the “iPhone country” and “chanson country” took place in Ukraine much earlier than in Russia, and much more successfully. It's funny, by the way, that on Maidan in 2013-2014, on the same side of the barricades there stood irreconcilable opponents, who only yesterday had accused each other of some simply outrageous bydlostry. And it was Maidan (the "revolution of hidnist’", "revolution of dignity") that was supposed to save forever, God knows how, Ukrainians from bydlostry and zhlobness.

Back in the years of Viktor Yushchenko's presidency, the Ukrainian Internet was blown up by a short film directed by Alexander Obraz – "Drifter" – about a man who came up with "a sure, albeit cruel way to fight bydlo and gopniks." The plot of the five-minute tape, on the one hand, is simple, on the other hand, it may well represent a new vector in cinema: perhaps for the first time a serial killer is an absolutely positive hero, fully approved by the filmmakers. But here, in any case, is the plot: every Friday, a resident of Kiev, twenty-five years old, gets into his inexpensive but decent car and leaves the capital. He goes to a place where no one knows him and cannot recognize him. In the first supermarket of a small town, he buys a simple snack, combines it with vodka he has stocked up in advance, and with a supermarket bag goes in search of adventure. He finds them, of course, not immediately, but nevertheless: a couple of local young people take off with his cheap phone, which the hero specially takes with him, and the bag of booze and snacks. Having received a couple of blows to the face, the hero shakes himself off and returns back to Kiev. What is all this for? It's very simple: instead of vodka in the bottle squeezed off him by the gopniks lies methyl alcohol. “I drive along the highway and enjoy the thought that somewhere a bydlo, smoking his way up to the sky, drinks his last fifty grams (a term for a glass of vodka). The next day, I work so well” - the hero shares his joy at the end of the film.

Strangely, this anti-human and absolutely idiotic story found a huge number of ardent fans. “That’s how it should be with them,” Ukrainian intellectuals wrote on their LiveJournal and Facebook. “The method is harsh, but what is to be done with bydlos and zhlobs? they asked each other. The question of who and why appointed them the spiritual elite, and other people - cattle, predictably did not arise for the debators. Nevertheless, a distinct sadomasochistic accent - first we will get hit in the face, and then we will kill the enemies ourselves - turned out to be quite prophetic in terms of relations between the future Maidanites and the police and other power structures.

Older and supposedly smarter people did not lag behind in the search for zhlobs. The Kievan “Journal of Cultural Resistance” (by self-determination, of course) “Sho” (the Ukrainian word for ‘What’), headed by the Russian-speaking poet – winner of the Grigorievskaya and many other Russian awards – Alexander Kabanov, devoted an entire issue to zhlobness, the topic that excites every Ukrainian soul. It offered to understand and evaluate the conditional zhlob and decide what to do with him. It is worth noting that there was no talk of re-education, it was about destruction or, at best, eviction from beautiful Kiev and from Ukraine in general.

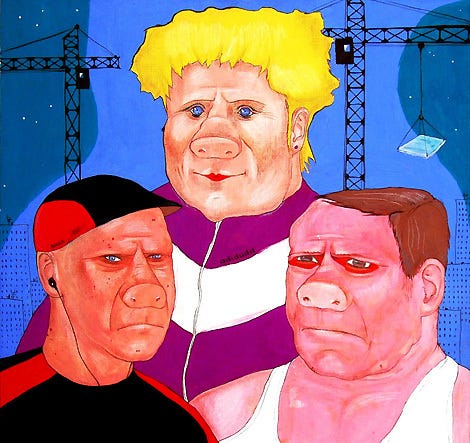

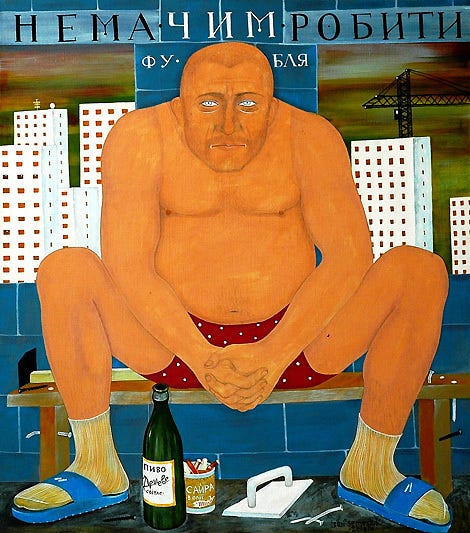

Almost at the same time, young Ukrainian artists - later their projects such as "Beware, Muscovites", representing people (Muscovites) in a cage, will enter the golden fund of the art of the "revolution of dignity" - Oleksa Mann, Ivan Semesyuk and showman Anton Mukharsky created a whole vector of Ukrainian contemporary art called "Zhlob-art". The semi-primitivist works of the “zhlobists” were intended to demonstrate to Ukrainian society all the leaden abominations of the life of “zhlobs” and “bydlo”. The Zhlob-art exhibition was an incredible success in Kiev: a huge number of the developed public aspired to look at the image of the life of the “little brothers”, who were not even brothers at all. Although what could be done for such a cultural project, except to hang mirrors around the hall? Wanting to condemn someone else's life, look first at your own face!

After almost fifteen years of life in Ukraine, I have not been able to find out who, after all, are the widely discussed and highly publicized representatives of the “zhloby” and “bydlos”. The original 1960s definition of zhlobs as people from villages who, for unclear reasons, moved to a big city, did not work in the 2000s, so the categories “zhlob” and “bydlo” entered into the realm of morality and ethics. And yet, these concepts lacked not only clear, but at minimum non-contradictory definitions.

The zhlob speaks only Ukrainian. The zhlob speaks only surzhik (Russian-Ukrainian creole). The zhlob does not know a single language, except for Russian. The zhlob came from the east of Ukraine, he also came from the west (in this case, he can still be called a “rogul”). The zhlob grew up in Kiev and now does not want to achieve anything, but only drink beer, because he is a zhlob. The zhlob taxi driver and the zhlob politician. The zhlob pays little and irregularly for work, but the zhlob also overpays other zhlob, because he is a lying sucker and a zhlob. The zhlob votes for Yanukovych because he is a gangster, for Yushchenko because he is the same rural zhlob, well, for Tymoshenko too, because she is a “good-looking broad”, but the zhlob goes and spoils the ballot in the elections because he cannot choose suitable candidates for himself. The zhlob wants to unite with Russia, and he also wants all the benefits of the European Union... The enumeration of the shortcomings of the conditional zhlob and the views attributed to him can be listed endlessly, although this does not add any understanding of the situation and the problem. There was only one thing clear in all this muddy stream of Ukrainian social thought: no matter the qualities of the zhlob and the bydlo, they are always worse than the one who dared to talk about them. And, of course, they are below him on the social ladder. Moreover, any reforms, revolutions and other transformations must be carried out not only without taking into account the opinions of " zhlobs" and "bydlos", but also specifically against them.

Sometimes, however, those who were considered to be bydlos and zhlobs became objects of national compassion and practically heroes.

First off, thank you for that Mikhail Krug video. I enjoyed watching it. Someone should subtitle that from start to finish. Unfortunately, my Russian isn't good enough.

Secondly, this story reminds me of the American 'deplorables', the difference being that these belong to a clear group, people from the heartland, voting for Donald Trump. In Ukraine, there seems to have been a real desire for an enemy, as if society was hollowed out by corruption and disappointment to the point that it wouldn't hold without one.

In that sense, the Russian invasion has been a blessing. Now there's a clear enemy, against which the people can unite. Only problem seems to be that Russia is so embedded in Ukraine, both linguistically and culturally.

It's also interesting to see the parallel with Western culture (or as you say: "Ukrainization of global political discourse"), of the superiority of liberal city dwellers. But perhaps this is a universal thing, and something that many leftist intellectuals struggle with. They feel that they are fighting for regular people, the unwashed masses, but at the same time they are appaled and repulsed by them. George Orwell comes to mind.

Great piece thank you for translating. Btw the paragraph ending in "from Ukraine in general" is repeated