Minsk series 3: Liberal disenfranchisement

Our first article in this series explored how Ukrainian liberal perceptions of the population of Donbass were determined by the assumption that the region was a cancerous trap threatening Euro-Atlantic integration. Our second article discussed propositions to abandon the region entirely.

Here, we will analyze propositions from the liberal pages of ‘Ukrainska Pravda’ (Ukrainian Truth, UP) and by other heroes of Euromaidan to restrict the voting rights of Ukrainian citizens in the Donbass. Where one UP writer in our last article recommended ‘gnawing off the paw stuck in the Donbass trap’, today we will have a look at propositions to keep the paw, but politically neuter it.

Post-2014 electoral disenfranchisement

Asides from the various ‘Democratic’ initiatives we are about to describe, limitation of electoral rights was a reality in Ukraine. Throughout the 2015-20 period, Ukraine’s more than 1.5 million IDPs (Internally Displaced People) were disenfranchised, banned from voting in local or one-member constituencies. This constituted over 4% of all voters. Their only way to vote in local elections was by registering in a government-controlled area, thereby ceasing to be an IDP.

The problem was that according to Ukrainian statistics, up to half of these registered IDPs actually lived in the territory controlled by the LPR/DPR, but acquired Ukrainian IDP status in order to acquire Ukrainian pensions and other state benefits. 51% of all registered IDPs were recorded as receiving pensions and other state benefits.

While Ukrainian benefits were miserable, L/DPR benefits were even lower, as befits a war-ravaged parastate. As a result, these IDPs constantly crossed the (highly dangerous and prone to excruciating traffic jams and delays) demarcation line to receive their benefits in territories controlled by the Ukrainian government, where they were registered as IDPs. OpenDemocracy has a good article regarding the hellish trips across the demarcation line that IDP pensioners had to make in order to receive pitiful pensions.

IDPs crossed the demarcation line not only for purposes of receiving benefits, but for other purposes as well. It is worthwhile reproducing the following fragment from a 2019 report commissioned by the Council of Europe – not least for its illustration of the misery IDPs were put through:

Territorially, over 50 per cent of all IDPs are concentrated in urban centres in the GCA [Government-Controlled Areas] of Donetsk and Luhansk, 9 per cent in the adjacent region of Kharkiv, and 12 per cent in the capital Kyiv. The rest of IDPs is distributed in the remaining regions, predominantly in eastern and central Ukraine. Large number of IDPs that are displaced (or registered to be displaced) in the GCA of Donetsk and Luhansk remain close to their original homes located in NGCA [Non-Government-Controlled Areas) in hope that they would be able to return home. They are often residing in GCA immediately surrounding the zones of ongoing military operations. Especially these IDPs, as well as de facto IDPs that are not registered and others, face chronic insecurity and limited access to water, electricity and medicine, and have inadequate access to livelihoods and shelter solutions. According to statistics, there are approximately half a million people living in these conditions along the contact line and around 30,000 people, many of whom are registered IDPs, reportedly cross the line every day. People go back and forth to insecure areas, including places where they face ongoing gunfight, landmines and little assistance, in order to visit their families, check on their homes or property, buy food and supplies or access their social benefits.’

Separated from their workplaces by a potentially deadly demarcation line, unemployment rates for IDPs were estimated at 25%, while national levels were 8%. Their electoral disenfranchisement, along with general chauvinism, also led them to be considered second-rate citizens in the communities they inhabited. They were also often subject to chauvinistic attacks by the government, with interior minister Arsen Avakov blaming ‘migrant-refugees’ from Donbass for crime rate increases in 2016.

Throughout the post-2014 period, and even after IDPs were granted the right to vote in local elections in 2020, regional elections in areas of Donbass controlled by Kyiv were routinely canceled due to so-called ‘terrorist threats’. OpenDemocracy notes that the ‘unofficial version’ explaining these cancellations was that president Poroshenko was worried because local residents kept re-electing ‘Nash Krai’, the Yanukovychite party in the region, with Poroshenko’s party getting almost no votes. As Nikolai Petru in his recent book ‘the Tragedy of Ukraine’ argues, Zelensky’s denial of the ability of Donbass citizens to vote in the 2020 and 2021 municipal and regional elections on ‘security grounds’ was seemingly contradicted by Zelensky’s simultaneous statement that ‘the region has never been safer’.

The dangers of democracy in Donbass

Our previous articles have explored the Ukrainian liberal argument according to which inhabitants of Donbass, if given political rights in Ukraine, would support political projects which would hinder Ukraine’s Euro-Atlantic integration. Here we will begin by simply listing several examples of liberal and mainstream Ukrainian media figures expressing their doubts about enfranchising the population of Donbass.

The last article analyzed an article about the dangers of implementing the Minsk agreements by Valeriy Pekar, an influential liberal journalist. Among its main worries was ‘the reintegration of the citizens of the liberated territories, their participation in central and regional elections. Think about who they will vote for, about how political activity works over there’.

Former president Leonid Kuchma in an interview about the peace process expressed the same fear regarding elections. If they were allowed to take place, the residents would ‘look towards Russia, not Kiev’, which he blames on the militarized nature of politics in the region.

In the words of one 2015 UP article regarding the latest news on the minsk agreements:

‘Where is the greatest danger? First of all, in the particularities of the election process in Donbas. Currently, there are almost no pro-Ukrainian residents left in the occupied territories - everyone who could, fled to "big Ukraine". And if their opinion is not taken into account, the result of the elections will be obvious - the legalization of the "DPR" and "LPR" with their worst elements.’

This fear of the fact that the Minsk agreements did not involve disenfranchisement of the Donbass was repeated in another UP article from 2015, which worried about how through Minsk, ‘the Kremlin is attempting to ‘stuff’ the uncontrolled territories back into Ukraine as is… with a ruined economy and infrastructure, a disloyal and even openly hostile population’

Vladimir Gorbach, an influential analyst at the institute of Euro-Atlantic cooperation whose work we also examined in our last article, wrote that integrating the L/DNR into Ukraine as per the minsk agreements would result in the ‘Russian special service not leaving the enclave…. A cancer on the body of Ukraine’. By ‘secret service members’, he meant the stridently pro-Russian, anti-EU/NATO leaders of the L/DNR. The anti-western electorate and political leaders of the region threatening Ukraine’s EU/NATO aspirations is what is meant by this ‘cancer’.

Siroid’s ‘deoccupation’ plan – destroy all the terrorists like the Americans do

Oksana Siroid, deputy speaker of the Verkhovna Rada from 2014, took a quite a ‘hardline’ stance against electoral rights in the Donbass. On the one hand, she may not seem to be a ‘liberal’ – since 2019 she has been leader of the ‘Self-Reliance’ or ‘Samopomich’ party, which is a rightwing Christian party that only enjoys electoral success in the west of Ukraine.

But in fact, Siroid is quite representative of the Ukrainian liberal class – educated in Canada, her party was an enthusiastic player in Euromaidan, relies largely on the political voices of NGOs and IT professionals, and from 2015-16 tried to form an alliance with former Georgian prime minister and NATO liberal warmonger Mikhail Saakashvili and the inter-fractional parliamentary group ‘Euro-optimists’.

Siroid, as befits her hardline nationalist party (in 2017, the party suggested building a wall around the L/DPR, a la Israel), didn’t intend to play softball with Donbass voters. Siroid’s 2016 article was concerned with making it clear that elections could only take place after the ‘deoccupation’ of Donbass. By this she meant ‘neutralization of fighters, terrorists, weapons arsenals, Kremlin agents’. The qualification of who was to be ‘neutralized’ was naturally quite open.

Only after this ‘deoccupation’ does she chronologically place the possibility of ‘political reintegration of Donbass’ and ‘reconciliation’. She attacks Minsk for its proposition to start ‘the other way round’ – elections, political integration before anything else.

The article is filled with pearls – ‘After the terrorist act in Paris the president of the USA said that all terrorists must be destroyed. Why should their terrorists be destroyed, but ours should be elected?’ The fear that there might be political subjectivization of Donbass, thereby turning it into a civil conflict and removing justification for western assistance, also preoccupies Siroid. To neutralize this danger, she recommends passing a law considering L/DNR to be under occupation, just as Crimea is (such a law was indeed passed in 2018). The rest of the article is dedicated to urging the arrest of more ‘terrorists’ within Ukraine itself.

Moroz: no need for common language after the Russian tanks leave

Viktor Moroz, a prolific UP writer, published a 2016 article on site titled ‘the Minsk Suitcase’. Asides from handwringing about how ‘miner pensions in Donbass are very high (around $80 USD a month)’ and that paying pensions to all Donbass locals would put ‘serious’ strain on Ukraine’s finances, Moroz’s main target is also Minsk’s formula of elections, then military control:

‘It is quite accurate to assume that after the removal of Russian heavy weaponry – tanks, artillery, multiple rocket launcher systems – it will be much easier to find a common language with the inhabitants of these particular regions, and it will be much harder to find on the territory of Donbass those people who, hiding behind Russian tanks, call themselves the people’s government at the moment’.

In other words, it is only possible to deal with the inhabitants of Donbass if they are unprotected. This is why Minsk’s stipulation to hold elections without the region being under military control by the Ukrainian army is not palatable. It would mean that the region would elect its own political representatives, and that they would possess elementary means of defending themselves from the will of the Kiev political establishment.

In the next sentence, the author asks: ‘But it’s another question whether we actually need to find any common language.’ Such a statement makes it quite clear why some inhabitants of the L/DNR territories would consider it important to be militarily defended by non-Kyivan forces. This is what Minsk’s stipulation regarding the creation of an autonomous ‘people’s militia’ controlled by Donbass regional government structures meant.

Moroz is at least honest about the situation on the ground, unlike most English-language communiques by Ukrainian representatives on the topic. According to him, ‘sociologists and eyewitnesses show that no matter how tired the inhabitants of Donbass are with war, the least they want is to return to Ukraine’.

Mustafa Naiem’s democratically anti-democratic demarche

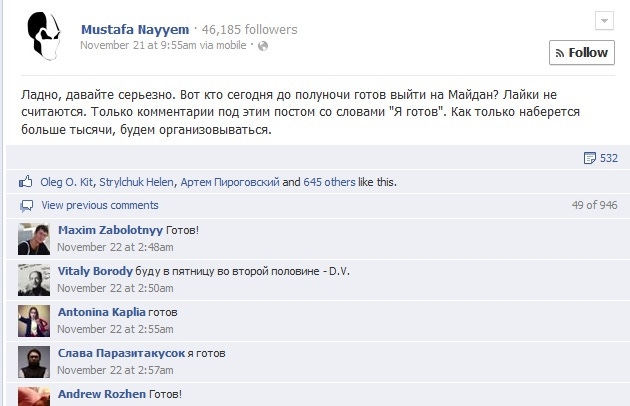

Mustafa Naiem will also be a subject of later articles. One could call him the human symbol of maidan. A journalist who spent most of his life substantially reliant on foreign paychecks. The Russian-speaking son of the Afghan health minister who quit his post in 1979 but nevertheless fled Afghanistan to Moscow in 1987. ‘The man who started euromaidan’, with a facebook post on 21 November 2013: Alright, let’s get serious. Who is ready today until midnight to go onto Maidan square? Likes don’t count/ Just comment under this post ‘I’m ready’. As soon as we get more than a thousand, we’ll organize it’.

After maidan, Naiem found himself a comfy spot at the Ukrainian state defence corporation, Ukroboronprom, where he supervised its steady (and not so steady) decline. A seat which, needless to say, he had no qualifications other than his civilizational choice against Asiatic corruption, as the phraseology in Ukraine goes.

Where this archetypal warrior for democracy enters our story is his opinions regarding the electoral rights of inhabitants of Donbass. Following maidan, he joined Petro Poroshenko’s party ‘European Solidarity’. At a 2017 conference dedicated to the ‘formulation of the peace [!] process in eastern Ukraine by politico-democratic means’, Naiem expressed his doubts regarding the need to allow IDPs that mostly live in L/DPR to vote.

Naiem began by explaining that ‘The region [Donbass] was handed over to the people who led there before the revolution. It's not bad and it's not good, but you have to admit that it happened.’ According to Naiem, the residents of Donbass will mainly vote for such ‘pre-revolutionary’ forces similar to or affiliated with Viktor Yanukovych. Here, the critique of bad IDPs is hard to disentangle from a critique of Donbass voters as a whole.

“One way or another, we must give these people the right to vote, because they must influence the political life of the areas where they live. At least at the local level, I'm not talking about the national level. But we must decide by what criterion. One of the criteria should be the center of vital interests. That is, if a person is registered in a certain region, and he can present a certificate [that he is an IDP], we will have no reason not to grant him the right to vote. Now imagine, these are hundreds of thousands of people registered as displaced persons in the controlled [by Kyiv] territories, but in fact they live in that [non-controlled, L/DPR] territory. Their center of vital interests is there. They somehow cooperate with that government (representatives of the L/DPR - ed.). And if we allow elections even at the local level, we will get in our territories not only a non-integrated government, but a government that will directly represent the interests of not quite Ukrainian forces.”

I bolded the relevant parts of Naiem’s quote. Here we have the usual fears of the voting habits of Donbass citizens, whose disagreement with the euro-atlantic consensus means that they are ‘not quite Ukrainian forces’.

Naiem also accused the political forces in charge of the regions of Donbass under Kyiv’s control to have ‘pro-separatist’ political views. A foreshadowing (not that it wasn’t going on already) of Zelensky’s 2021 moves to sanction and otherwise ban some of (if not the most) the most popular national political parties (such as Medvedchuk’s Opposition Platform for Life – OPFL) representing inhabitants of south-east Ukraine.

‘Nash Krai’, which loosely translates as ‘Our Region’, the Donbass party criticized by Naiem, was similar to the OPFL in that its orientation towards the voters of the south-east meant that it was not chauvinistically nationalistic or enthusiastic about liberal economic reforms. As we have already seen, Naiem’s recommendations to repress this party weren’t without precedent in reality – the Poroshenko and Zelensky governments often cancelled elections in the region due to fear of Nash Krai’s popularity.

There are two more important facts surrounding Naiem’s proposal. First, that this came in the context of Kurt Walker’s (US special rep for Ukraine negotiations) statement that ‘a series of elections’ should take place following the intervention of peacemakers. Even this recommendation, not entirely in the spirit of the Minsk agreements (which do not mention peacemakers), made Naiem’s democratic heart seize up with fear of the spectre of Donbass voters.

Second, that Naiem’s statement met with harsh criticism from a judge from Ukraine’s Supreme Court, Vasiliy Gumenyuk, who pointed out the unconstitutional nature of Naiem’s proposal. Ukraine’s top juridical structures have long caused irritation to euromaidan’s ‘brave young reformers’, due to their tendency to remind the reformers of things like the Ukrainian constitution. I have written about this struggle elsewhere, as have other authors.

Naiem’s ‘principled opposition’ to the voting rights of more than 1.5 million people might seem to be in contradiction with the much-vaunted ‘democratic ideals of Euromaidan’. In fact, this living embodiment of Euromaidan was quite consistent with his ‘European Values’. As we have argued throughout this series, the Ukrainian liberal unwillingness to implement the Minsk agreements came from their fear that the political subjectification of the Donbass would halt Ukraine’s integration into the EU and NATO. Or at least (since EU or NATO integration was never too likely), these voters would stop liberal economic reforms and the claims to political power by figures such as Naiem.

Arsen Avakov’s peace plan: the good example of Franco’s Spain

Arsen Avakov is another symbol of maidan. A Russian-speaking Armenian businessman active in the Kharkov region throughout the 2000s, he fostered far-right football hooligans to take care of his business disagreements on the streets (see Colborne’s 2022 book From the Fires of War: Ukraine’s Azov Movement for more on this).

Exiled by Yanukovych, Avakov returned during maidan, playing an important role in the sniper massacre. Playing an important role in the repression of the anti-maidan movement in Kharkov, he took the post of internal minister, a post he held for a record 7 years. Throughout this time, it is no exaggeration to call him the ‘grey eminence that controlled what might be called the post-2014 monopoly on violence – or at least held a controlling interest on it. Or as a 2020 Polish article was titled, ‘a Pillar of the System: the Phenomenon of Arsen Avakov’.

Following maidan, he directed the east Ukrainian rightwingers he had employed for years to fight against separatists. It was he who essentially created the Azov batallion, which he reintegrated into the Ukrainian state under his control as the newly created ‘National Guard’. He played a strategic masterstroke in those years – by sending bloodied maidan revolutionaries to fight in the east, he neutralized a dangerous threat to the new maidan government, which would often be critiqued by surviving radicals for ‘betraying the revolution’. Those radicals which were out of control, such as Sashko Bilyi or the Tornado Batallion, were accordingly liquidated by Avakov, sometimes physically.

From 2014 onwards, his office was a key destination for anyone in Ukraine who wished to play politics. He was the head of a huge pyramid – or web – of nationalist paramilitaries who constantly violently threatened and attacked political opponents and the government. His power was such that he is commonly credited with stopping Poroshenko’s attempt at fraudulent re-election in 2019.

Educated as an engineer, he represents that cynical, cunning class of late-soviet businessmen that would prove willing to use all variety of extreme nationalists to acquire the political power required to defend economic assets. This, despite Avakov’s own patent cosmopolitanism.

Avakov explained his ‘peace plan’ for the Donbass numerous times. An article recently translated on this blog examined some of Avakov’s propositions on this topic. This article will focus on his 2018 interview with UP titled ‘I have a plan. First we take just Gorlovka’. The title refers to his rather strange military strategy, according to which the Ukrainian army should gradually retake control of the L/DNR, piecemeal, city by city.

In other facebook posts, he favorably brought up the example of post-WW2 France, in which ‘9000 collaborators were lynched without a court’ and ‘3920 were executed’. The comparison between dissident inhabitants of the Donbass and fascist collaborators in WW2 gives the reader a good idea regarding Avakov’s willingness to politically engage with the region.

In his 2018 interview he also insists on the need to punish ‘collaborators’ in the region, and ensure that all ‘Russian agents’ leave forever. But as a result, he claims that ‘transitional positions’ regarding special status for the Russian language or a special economic zone need not matter -‘This is a matter of much more important institutions, of the success of state-building in Ukraine’. As long as the key political leaders leave or are arrested – he mentions the Donetsk-born Alexander Zakharchenko, then-leader of the DPR – local political concessions to popular demands are palatable.

In a sense, Avakov’s position had its ‘liberal’ aspects. It is hard to find other representatives of mainstream Ukrainian politics who declared themselves fine with Russian language minority rights and other autonomy rights. But this exception proves the rule, in that Avakov shared one key concern with the rest of the political class – preventing the reintegrated Donbass from influencing Ukrainian politics at the state level.