The post-soviet philosophy of history

Postmodern peasants. Apocalypse, contingency and necessity. History and I. EH Carr, Karl Popper and George Soros.

No one pays attention to these killings, but the secret of the world is hidden in them - 2666

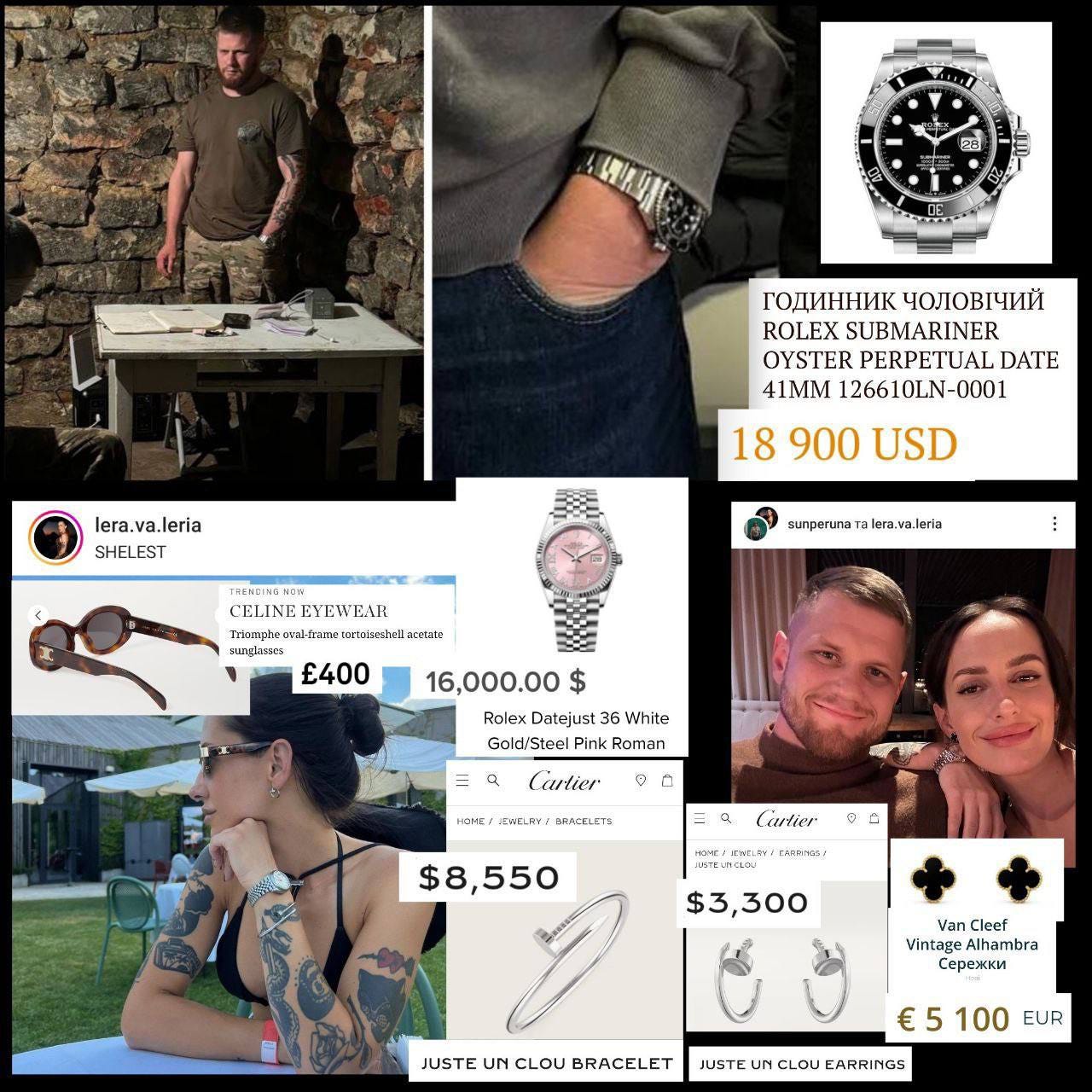

I decided to write this post because I finally set about reading EH Carr’s classic book, What is History. I had long been a great fan of Carr’s historical work on the Russian revolution and Soviet state-building, though I never found the time to progress beyond the first volumes.

Some online friends have been raving about Carr a great deal lately - one of them is on substack, the fantastic Rob Ashlar - but the specific impetus to read Carr came from another source. It was from a Trotskyist historian, John Abel, who I met at a weekly pub get together. Political differences notwithstanding, we found a common language in discussing history. Specifically, that of eastern Poland - where he is from, and I have spent some time in - and western Ukraine. After the pub, I read an article by him on Carr, focusing in particular on What is History.

What is History, a series of lectures delivered in 1961, essentially riffs on the complex dialectic between the historian and history. The meaning of historical ‘facts’, subjectivism versus positivism, the context and viewpoints of the historian in determining the history written. As Abel writes, the essay set the framework of all subsequent debate on the topic.

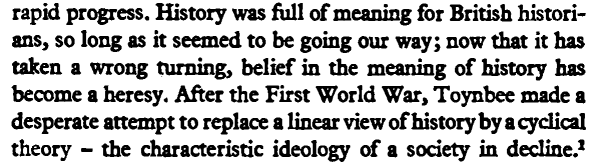

I found Carr’s thoughts on cyclical and progressive theories of history particularly interesting:

I have always had a proclivity for cyclical theories of history - perhaps because I’ve spent my life in societies of stagnation or catastrophic decline - and hence I immediately disagreed with this passage.

Doesn’t it itself imply a cyclical theory of history? Societies rise and fall, and during the growth period of the cycle, their historians calmly defend positivistic, progressive theories of history, and during the decline period, they hysterically criticize positivism and extoll subjectivist theories of decline.

But on the other hand, one could also extract a more dialectical reading. Perhaps each declining civilization only beckons the emergence of a new, stronger one. Carr The British empire made way for the US ‘rules-based order’. And if British intellectuals were quite pessimistic in the 60s, when Carr was writing, there was still plenty of optimism among their colleagues across the Atlantic.

And as Carr himself wrote, the pessimism of the west is itself only the counterpart of the optimism of the emerging Third World. A statement which is truer today than ever before - one only has to read the statements of Chairman Xi Jinping.

Teleology

Things are a great deal stranger in that part of the world which has struggled so much with its national identity, its peculiar location between the fading west and the rising east - Russia and Ukraine. I won’t try capture the complexity of modern Russian state ideology, which I am not qualified to do. I also fear it could be an even harder task than understanding contemporary Ukraine’s philosophy of history.

In any case, Ukraine’s hegemonic theory of history presents not a few paradoxes. To begin with, it manages to be at once totally teleological and completely postmodern.

Teleological in the sense that it is a given that Europe with a capital E is identical with Civilization, that no country has ever Developed without adopting wholesale ‘Western models’, that European Values represent the accumulated knowledge of all human history, and so on and so forth.

The average Ukrainian liberal believes in Western Values far more stridently than anyone actually living in the west. In the same way that these same Ukrainian liberals will claim that the only lovers of communism are those that don’t live in post-communist countries.

Regardless of the truth of that last statement, I can definitely say that public discourse in the west is far more technocratic and unromantic than Ukraine’s - though there are no shortage of attempts lately to ‘Ukrainize’ western political thought, so to speak. ‘How I learned to stop worrying and love the West’ - how many think pieces in favor of ‘supporting Ukraine’ have been written in western publications since 2022 with this argument? ‘I had given up on the west until the Ukrainians showed me how important it is to believe’. See, for instance, the Atlantic:

If this Ukrainization is fully successful, perhaps one could see an end to the guilt and doubt that periodically nags western consciences (not that I’ve noticed it)? There are many who ardently campaign for such a historical reassessment (or reaction), along with other ‘defenders of western values against barbarianism’. Though, it must be said, all the Robert Kagans and Benjamin Netanyahus never suffered from much doubt in Western superiority.

Postmodern peasants

But at the same time, actually living in Ukraine, one gets the feeling that there is no more cynical, unbelieving society on earth. I have written here before about the phenomenon of Ukrainian ‘khatastkrainichestvo’ - ‘my house at the edge of the village’, where individualistic egoism takes precedence above all else. Any ideology whatsoever can be assumed - as long as you stay off my lawn.

But it isn’t just that ‘eternal individualism of the black earth peasant’ (which is just as often used for those living in the black sea regions of southern Russia). Ukraine is just as postmodern as it is post-soviet. Western intellectuals often defined the postmodern as the collapse of grand narratives, mainly that of Marxism (since liberal teleology certainly never died…)

But how much was that really an event in the west? Did the collapse of Marxist ideology have such a great influence on how average citizens of the western countries lived and died? Sure, the end of the Soviet Union made it easier to abandon social democratic policies. But did the average person in the Rust Belt or Manchester really care that much about the end of the Soviet Union, the end of Marxism?

A certain decline in western living standards in the neoliberal, post-1991 era - itself debatable and dependent on the western country in question - is nothing compared to what citizens of the former Soviet Union lived through. According to one recent study, 7 million died due to the economic shock therapy of the 90s in Russia, Belarus and Hungary. There is no comparable example in western history of peacetime decline in life expectancy.

Some might call that ‘the cost of change’. I, for instance, do indeed subscribe to the idea that the famine suffered by the Soviet Union in 1932-3 was a necessary cost in the context of an imminent genocidal invasion, and given the rise in average lifespan from 30 in 1914 to 50 in 1950. A topic for an upcoming post.

In the 1990s, ‘brave reformers’ from Yeltsin to Gaidar to Chubais also promised imminent convergence with western living standards following economic liberalization. Some ‘temporary pain’ was necessary in the name of such lofty goals.

But as everyone knows - not that any of those responsible have ever felt guilty about it - they were wrong. There were very high costs, a great deal of pain - but no payoff.

Ukraine didn’t undergo the same level of privatization and liberal shock therapy that Russia did in the 1990s. For Ukraine, it began in the 2000s and continues to this day. The 2014 euromaidan, with its laughably earnest - but ever so depressing - promises from the likes of Yatsenyyuk to ‘lift Ukraine’s wages to German levels’ - immeasurably accelerated this process.

Naturally, liberal privatization in Ukraine, just as much as in Russia, created an immense feeling of disappointment, an anger at having been tricked. My old interview with a Ukrainian trade unionist went into this, though he certainly denied ever having been caught in grips of euro-illusions:

Me: Did or do you know anyone among your colleagues that was enthusiastic about EU-integration?

Kolya: We work with one guy, Vasya. He always thought that he’d be able to export the cucumbers he grows to the Germans. So he loved the idea. He still thinks that. You know, there are always some retards (debili), everywhere.

Me: So how did EU-integration change Ukraine?

Kolya: Well first of all, there has never been any ‘EU-integration’. They just get access to our markets, and we can’t sell much to them.

How has it changed things? Well, I don’t know, we have some gay parades, but a lot less industry and jobs.

Despite threats and repression, there was no shortage of talented economic journalists in post-2014 Ukraine that acutely and ironically criticized the empty promises of euromaidanite economic shock therapy. Dmytry Dzhangirov and Roman Gubriienko were particularly inspiring for me. Dzhangirov, an old, ironic man, was humiliated on camera at the start of the war in his pajamas, and never heard from again.

Gubriienko is doing better, but has been put on a liberal-nationalist (USAID-funded) NGO hitlist for ‘leftwing ideology and supporting the USSR’. Gubriienko’s countless fantastic articles of economic journalism no longer exist, since the website he used to write for (vesti.com) has self-censured anything which seems critical of euro-atlantic common sense (none of the articles had anything to do with Russia, mind you).

My point is that Ukraine is a country which has felt the loss of grand narratives far more than the west. Ukraine spent almost a century in the avant-garde of the Soviet project. It was the scene of the greatest battles of both 1917-1920, and 1941-1945, those wars that did just as much to form Soviet identity as the collectivization and industrialization campaigns. And as Ukrainian nationalist sociologists never tire of lamenting, the Donbass was not just the most Soviet part of Soviet Ukraine - it was the most Soviet part of the Soviet Union. These were multinational, proletarian regions whose citizens took pride in building an industrialized Socialist modernity.

It unceremoniously lost this great project, then adopted a new free market utopia. And in the second case, the masses paid a higher price, but with no payoff. And right after abandoning Soviet modernity, its intellectuals and state propagandists - almost all of whom were until then enthusiastic Soviet propagandists - began their never-ending, publicly broadcasted wallowing in the horror of communist oppression. And corresponding glorification of individualism - a life without narratives other than nationally conscious, peasant ideals.

A third grand narrative enters the stage! Given how disappointing and bland liberal euro-optimism is, it needs a bit of sauce - blood and soil. Not satisfied with being a condiment, this teleology is perhaps Ukraine’s most dramatic.

In fact, there is no shortage of modern Ukrainian public figures who make the claim that ‘Ukrainian nationalism is just a perverted form of Soviet totalitarianism’. A claim I’d take issue with, given that the Soviet project boasted a great deal more ideological content, coherence, and constructive results.

Let’s take a moment to contemplate this rather schizophrenic coexistence of opposites. Postmodern cynicism seasoned with with barely secular Euro-Optimism, all mixed through with some ultranationalist flour to keep it together.

It’s time to die for a motherland, a state which for the past 30 years has never stopped drumming on about how all state assistance to its citizens is retrograde, harmful and totalitarian. A social Darwinism which has only grown louder in wartime - according to the education minister in a BBC interview two weeks ago, it would take 50-60 billion USD in foreign aid to raise teachers’ salaries. As he ruefully admitted, they are currently ‘socially marginalized’, making only 6 thousand hryvnia a month - $145 USD. But in the minister’s words, military spending takes priority. As if teachers earned much more before the war.

In fact, it isn’t enough to get rid of critics like Dzhangirov for the Ukrainian philosophy of history to convince everyone. Ruslan Bortnyk, a Ukrainian sociologist, said in a talk show on last week that the devastating rocket attack on the Poltava military school was certainly facilitated by a ‘local traitors’. He criticized the government’s current strategy of harshly repressing such figures, and instead called for a different social policy to ‘keep those on the margins of society from working with the enemy.’

Indeed, those arrested for attacking military vehicles or ‘collaborationism’ are often unemployed, on a $100 pension, or earning little more than teachers. Given the fact that the Ukrainian state has never helped them, why not accept a comparatively astronomical $500, $1000 from an FSB agent on telegram?

Apocalypse now

It’s hard to sum up Ukraine’s current theory of history. The inconsistency and frailness of this worldview is probably what makes it necessary to silence dissident voices like Gubriienko and Dzhangirov.

Perhaps it is cyclical, insofar as its intellectuals consider all historical and present-day events to be determined by the endless struggle between freedom-loving Ukrainians and mongoloid Russian slave-society. But it’s also so very progressive in its Eurocentrism.

But it’s teleological in another, more medieval sense - in its apocalypticism. Bandera and Shukhevych were very fond of the idea of a third world war, which they saw - correctly - as the only way to defeat the Soviet Union, and win Ukraine for themselves in the ashes. Shukhevych even said that half of all Ukrainians might have to die in order to reach true, anti-communist freedom. Apocalyptic not only with regard to Ukraine, but most of all Russia, regarding which any ‘conscious Ukrainian’ is sure will collapse imminently, as I wrote in more detail here.

I’m reminded of the popularity of the telegram group/meme - ‘gather at naked mountain for an orgy after the nuclear war’. The trend started in mid-2022, and everyone from celebrity chef/sadist Klopotenko to presidential advisor Arestovych joined in.

Or the popularity among Ukrainian military nationalists of fantasizing about a post-armaggeddon mad-max Reich:

But overall, Ukraine’s discourse is much more implicitly apocalyptic than Russia’s. There, the risks aren’t swept under the rug. We’ll go to heaven like martyrs, but they’ll just croak, as Putin famously said in 2018. It seems like the alternative is either to make the end of the world a joke or to glorify it. Or maybe that’s the difference between geopolitical passivity and subjectivity.

Lately, Zelensky and his diplomats have started particularly shrilly demanding m ore long-range missiles. As of today, it seems like his dear western partners will indulge him. This should make little sense - what possible military impact could this realistically have?

But Ukrainian analysts like Ruslan Bortnyk see the real causes quite clearly - as an attempt to get the west directly involved in the war in Ukraine with boots on the ground and Russian strikes on NATO countries. The only way to turn the tides of war in Ukraine’s favour.

Contingency and progress

EH Carr didn’t believe nuclear war to be particularly likely. But discussion of the apocalypse does lead onto one of the main topics of What is History - chance and cause in history.

From what I’ve said so far, it might seem like the Ukrainian government doesn’t take nuclear war particularly seriously. And not a day goes by without Ukrainian diplomats castigating the west for believing in ‘Putin’s red lines’ - we in Ukraine have known them to be fake for years now!

But there are other signs as well. On August 16, Ukraine’s Cabinet quietly adopted Resolution No. 936, necessitating local government organs to provide citizens with ‘gas masks in case of a nuclear attack or the use of other weapons of mass destruction’. So maybe Russian red lines could exist?

This ambiguity comes from the fact that modern Ukraine has a true phobia, or rather hatred of the very idea of cause and effect. The apocalypse might come, and if so it will be totally out of our control, caused by an irrational, hateful god - Putler.

This looks much more like theology than history, replete with its own eternally suffering Christ figure, that of Ukraine. Any attempts to inquire into causes are blasphemous treason. In reality, attempts to forget about causes only make the inevitable effects even more shocking and unpleasant.

Carr defends the historian’s duty to seek out cause and effect against the irrationality so popular in contemporary western thought. But a subsequent argument I find harder to apply regards progress. He takes aim at the ever-popular western prophets of decline. Correctly diagnosing them as simply the expression of dying, reactionary classes who see no place for themselves in modern progress, he posits that progress continues, but in the third world.

Globally certainly, but in Ukraine it’s hard to believe in progress. Nor that all those nostalgic for past eras are necessarily reactionary classes, or that those who believe in progress are themselves progressive. In any case, Carr makes the important admission that history has periods of regression on the backdrop of global progress. Not only temporally, but also geographically.

History and I

While Carr is no relativist, he is adamant that there is no separating the history written from the historian. So for those interested, I will go into the way that Ukraine has shaped my own thought.

When living and talking with my Ukrainian family and friends, I was somewhat shocked by the degree of khatastkrainik cynicism. When I as a teenage undergraduate read the Marxist literature so normal in western university campuses in Kiev or Kharkov, my family excoriated me.

In the west, it is normal to believe in all sorts of high-minded ideals, but not to pay too much attention to them in practice. In Ukraine, my high-minded rhetoric was made fun of and dismissed. The only ideal possible, they claimed, was to earn enough money to live comfortably, and ideally escape the country.

But I hold no ill will on this account - I have found much more satisfaction analyzing the concrete instead of pondering the abstract. Living in the ahistorical west, I, like my peers, was mainly interested in philosophy. When I moved to Ukraine, I brought a great deal of books with me, mainly the philosophy I was so engrossed by. But within several weeks, I never opened another page of philosophy.

One of the catalyzing moments was a late night trip to the supermarket - I encountered a drunk man in a bloody heap, kicked enthusiastically by a security guard. I tried to help the man - it turned out we shared the same name. He told me he was from the industrial city of Krivoy Rog, and had come to the capital in search of work, but found none. I tried to carry him back to his hostel, but he couldn’t stand up and simply pleaded with me to buy him more vodka.

Faced with my powerlessness, I sent an angry message to my father, who played his fair share in the collapse of the Soviet Union and as a capitalist propagandist. To bring things back to Carr, who extensively critiques the sophist in question, one of my father’s several world-historical crimes was his translation into Russian of Karl Popper’s critiques of Hegel in the 90s - on Soros grant money.

Faced with such everyday displays of violence, as well as by my growing interest in the effects and origins of the Euromaidan my parents had, after all dragged me to in 2014, I lost interest in philosophy. In a country where a revolution in favor of ethnonationalist neoliberalism had won, I found little comfort in abstract schemes extolling Revolution with a capital R. It seemed much more important to focus on the concrete in a country where terrible things are committed in the name of the most noble, abstract ‘Values’.

For the next several years, I became absorbed by world systems analysis and the theory of unequal exchange, which was very relevant in understanding Ukraine’s relationship with the EU. Then, from 2022 onwards, I turned more towards history, particularly military history.

In fact, I moved to Ukraine out of a certain desire to be ‘close to history’. As a student, my theoretical enquiries kept on drawing my back to ‘History’, its existence or inexistence. Whenever I went to Ukraine to see family, I felt myself immersed in a place where historical facts are made - quite intoxicating. Nothing was more interesting that simply seeing the history happening. Circular abstract questions became very boring in comparison.

Leaving the country was quite devastating to me because I felt I had lost touch with history, with reality, or the Real. On the other hand, I remember being in Kiev at the end of February 2022 somewhat regretting my interest in locating myself on the historical stage, so to speak.

Writing this substack has cheered me up by connecting me to the history that is taking place so far away from me. And perhaps with a certain distance, it becomes a bit easier to wonder about the meaning of it all.

I've felt the same way living in the west around constant rejection of reality by my peers. The casual denial of cause and effect towards events that occur was a passage that resonated deeply.

Recently there was a fascist march in my city of Glasgow and our anti-fascists outnumbered them 10 to 1. This was seen as a great victory and there is hostility, and also just confusion, when I say it was a failure on our part. We failed to get a group ten times smaller than us off the board and couldn't even organise against a police kettle of friendly football ultras. I'm told to stop being pessimistic or a shrug of what can we do which reads quite comfortably onto your ideas about cause and effect being a heresy

I used to nore this very strange allergy to cause and effect among Russian liberals (back when there was such a thing in the wild and not just in museums of paleontology). I speculate that it is because they are adhering to an ideology that has no basis in their own lived experience, or in their history as a people (so that it would have some relation to material reality), but is purely an import. ?