This article is the second in my series examining currently popular ideas about how Ukraine’s geopolitical importance to the US-led western bloc will supposedly influence post-war economic development in Ukraine. The first article was about the ‘Ukrainian Marshall plan’. This one is about the Ukraine-South Korea comparison. The next will be about the idea of Ukrainian EU-integration.

A definition of ‘economic development’, that I will use throughout this article: I define it as constant wage growth based on extensive industrialization (new factories) and intensive mechanization (more productive productive techniques, specialization in sectors requiring higher skill levels).

The comparison

The Ukrainian economist Alexey Kusch recently posted on Facebook what Ukraine should learn from the economic development of the Republic of Korea (South Korea).

According to him, the ROK following the Korean War of the 1950s was similar to post-2014 and post-2022 Ukraine. The Korean peninsula was divided due to the struggle between two rival geopolitical blocs, with the ROK remaining after the Korean war as a pro-US capitalist nation. No matter how the current war ends, it will end with part of Ukrainian territory remaining pro-Western. These territories will be on constant military alert and will spend a great deal on the army due to the threat of renewed hostilities with Russia and the ‘other Ukraine’. Its economy will be devastated by war, and it will have lost many of its its most industrialized eastern regions to Russia (just as the ROK lost the industrialized north to the DPRK).

Kusch also draws a comparison between post-2014 Ukraine and the ROK during the reign of Syngman Rhee (1948-1960). As Kusch writes, the economic model was guided by the slogans of ‘help us more, interfere less’ and ‘give us what Japan has, now’. Both countries were ruled by a corrupt domestic oligarchy, liberal bureaucrats chosen by the West, with politics and economics highly influenced by the whims of military groups. The American patrons of both countries had essentially given up on both countries. One recalls the American-born, IMF-favorite Natalie Jaresco’s frustrated resignation from the Ukrainian ministry of finance in 2016 due to Ukrainian corruption and politico-military intrigues preventing her establishment of a properly ‘technocratic government’, and the belief by US state advisors in Seoul in the late 1950s that the ROK was a hopeless basket-case1.

Kusch even draws a direct parallel between the ‘village-kulak style ethnonationalism’ of the Rhee-era ROK with that of post-maidan Ukraine. In the ROK and Ukraine the poverty of the masses was generally blamed on the ‘colonial legacy’ of the Japanese or Russians, with political or economic rivals vilified as ‘serving the oppressor’.

Finally, while the US gave plenty of ‘aid’ to the ROK, this was either embezzled by local bureaucrats or spent on buying American weapons and agricultural goods. In both cases as credit that had to be repaid with interest. Just like Ukraine does, though more with various military goods and macroeconomic financial support than agricultural goods. Finally, Kusch points out the similar economic basis of both regimes – export of raw materials with minimal domestic value-added.

To sum up, both the Rhee-era ROK and post-maidan Ukraine were/are characterized by economic liberalism, corruption, and economic stagnation. Despite or because of their geopolitical importance to the US and their preferential position as recipients of Western ‘aid’, their economies stagnated or even declined.

So far, the analogy is entirely correct. The important part is where Kusch outlines what he thinks Ukraine should learn from the post-Rhee period of the ROK – the Park Chung-Hee period (1961-1979):

According to Kusch, the ROK went from a low-wage, agricultural society to a relatively high-wage, industrially advanced society for two reasons – the wise economic policies of the military dictator Park Chung-Hee, who took power in 1961, and the ROK’s privileged access to US markets. Kusch thinks that Ukraine should learn from how Park ‘rebuilt the state on the platform of economic nationalism’. He summarizes this approach as one where ‘we, Koreans, know best how to build our factories and reform our economy, and while we appreciate the help you, the USA, can give us, the best help you can give is to open your markets to our products’. Kusch cites the Park regimes Five-Year Plans as an example of the economic nationalism that supposedly catapulted the ROK to economic prosperity. We will see later on just how little connection these plans had to economic reality, which developed according to interests outside of the power of the ROK elite.

Kusch’s assumption about ROK development

First, we should note that Kusch’s analysis contradicts itself, because while he notes that the ROK was a poor, stagnating country throughout the 1950s and in the early 1960s, he also claims that ‘the most important factor [in the economic growth of West Germany, South Korea and post-war Japan] was access to the US market’. But throughout the 1950s and early 1960s, the ROK had preferential access to the US market. So the crux of Kusch’s argument about the ROK’s economic growth must be his praise for Park Chung-Hee’s economic nationalism and state economic interventionism.

For Kusch, ROK economic development out of backwardness was essentially due to a change in the elite. This is an analysis that pays attention to the internal factors. There was a bad elite in the 50s and early 60s, then a good elite came along, that took economic statecraft seriously. This is a very popular perspective in the post-soviet world, which can integrate both IMF technocratic word-porridge about ‘corruption’ and populist slogans about the evil people ‘up top’ (Jews, masons, Sorosites, Russians etc) that need to be replaced by a harsh but wise father of the people. Bandera priide, poryadok navede (Bandera will come, order will come) – or maybe Pinochet will, so beloved by the late- and post-soviet ‘liberal intelligentsia’.

The problem with the internalist explanation

Unfortunately for Kusch, economic historians have exhaustively shown that this ‘internalist’ explanation of the ROK’s post-1960 economic development is baseless. As Vivek Chibber2 notes in his comparative study of ROK and Indian 20th century economic development, both countries had a broadly similar politico-economic elite which espoused a combination of state-interventionism and export-promotion. Indeed, most third world countries in the 1960s and 1970s, let alone today, implemented economic policies broadly similar to that of the Park Chung-Hee’s ROK. But only the ROK truly industrialized.

The other problem for internalist, statist interpretations like that of Kusch is that Park’s famed Five-Year Plans, just like India’s Planning Commission, set up in 1950, had very little influence over the real economy (as we will see shortly in the ROK). These were simply goals set by the government - the economy remained in the hands of private investors, and the real economy often dramatically deviated from the ‘plan’.

If the ROK state was not in control of the dramatic post-1960s industrialization, then which private actors were, and why were they interested in it?

And if the ROK state was not all that different from other third world countries of the period, then what was the real difference between it and, say, India?

The answer to these questions is the ROK’s sheer geographical luck of being located near Japan. Japan and the ROK reconciled in 1965, prior to which the two countries had remained isolated due to the Korean trauma of Japanese imperialism. As the economic historian Robert Castley concludes his magisterial Korea’s Economic Miracle: the Crucial Role of Japan –

Very few other developing countries outside South-East Asia have the advantages possessed by the ASEAN countries, in particular the critical linkage with Japan and the Newly Industrialized Countries [ROK, Vietnam, China], the world's most dynamic economies. Hence, economists and international agencies who advocate Korea as a 'model' for developing countries in other regions would need to reconsider their advice.3

Japanese motivations

Japan played such a crucial role in ROK industrialization because of a set of quite unique factors that were explicitly recognized and acted upon by the Japanese state. Korea and Japan agreed in October 1965 to an international division of labor in which 'Japan would sub-contract out to Korea its labor-intensive export-oriented processing industries which in Japan were in decline’4.

In the early 1960s, it became clear to the Japanese Ministry of International Trade and Industry (MITI) that the Japanese economy had to expand outwards and domestically restructure to survive5. Japanese competitiveness, hitherto founded on low wages and labor-intensive exports, was becoming seriously threatened for the following reasons:

(1)

- Rising Japanese wages due to the labor movement and the post-WW2 Japanese political structure

- Competition in Japan’s traditional labor-intensive sectors from lower-wage producers in Taiwan and Hong Kong

- Rising environmental taxes in Japan after public reaction to the ecological problems caused by industrialization

- Sudden appreciation of the yen due to ‘shock’ devaluation of the dollar by Nixon, making Japanese enterprises less competitive

These factors motivated Japan to relocate its old labor-intensive sectors to a lower-wage country. That way, Japan would continue receiving revenue from this sector, although the Japanese workers formerly in these sectors would have to find new jobs.

(2)

- US tariff walls on Japanese textile exports in the early 1960s. This was a reaction to Japanese exports putting pressure on US employment, reminiscent of the anti-China trade war pushed by the US in recent years.

This factor pushed Japan to begin producing in a country that still enjoyed favored access to the US market – the ROK.

MITI also advocated the economic development of ROK for broader reasons. Japan didn’t require the ROK simply as a manufacturing center– if it had, the ROK would have remained a fairly impoverished low-wage nation, albeit which produced shirts for export – like Bangladesh today. Japan also wanted ROK purchasing power to grow, so that they could buy Japanese goods. The closure of much of the once-important US market to Japanese exporters required the ‘creation’ of a new export market.

Japan didn’t only want the ROK to buy Japanese consumer goods - they wanted the ROK to buy Japanese industrial goods. As MITI noted in 1977 'the expanding textile industry in developing countries will eventually translate into increased exports of Japanese textile machinery and thus play a significant role in the improvement of this country's industrial structure'6. Japan was hence eager for the ROK to industrialize in the 60s and 70s, since it was doing so by buying Japanese capital goods, as we will soon see. For much of the 60s and 70s, a triangular trading pattern emerged, whereby the ROK had a trade deficit with Japan which was made up for through a trade surplus with Europe and the USA.

(3)

- Long-standing ties between the Japanese and Korean elite, created during the period of Japanese colonization. Many Korean politicians, military figures and businessmen knew the Japanese language and kept in contact with the Japanese elite.

- Geographical proximity - Korea is only 200 kilometres from the western coast of Japan with the industrial zones of Masan, Pusan, Vlsan, Changwon and Pohang, all in the south-east corner of Korea, facing the Japanese ports and industrial centres of Kita Kyushu and Fukuoka, which had direct rail-links with Hiroshima and Osaka.

These were some of the ‘pull’ factors explaining why Japan chose the ROK in particular to relocate its old production.

Because of all the above, in the 1960s Japan transferred its textile industry to the ROK, while Japan reoriented towards higher-skill sectors where it would only face competition from high-wage countries. This allowed Japanese wages to keep growing – by specializing in sectors such as synthetic fibres and car manufacturing in the 60s, then consumer electronics in the 70s and 80s. In the 1970s and 80s, Japan transferred many of its heavy industrial sectors to the ROK, since this sector was also becoming outdated because of Japan’s growing wages. Because of this specialization in new sectors, Japan did not face competition from the ROK, nor were Japanese workers left unemployed by the relocation of Japanese.

All this was put quite poetically by the Vice Minister of MITI - 'it is by giving away industries to other countries much as big brother gives his outgrown clothes to his younger brother [that] ... a country's own industries become more sophisticated'7.

What about the USA?

Before we go into further detail about Japanese involvement in ROK industrialization, it’s worth outlining a good example of ineffective economic aid. Before we go into further detail about Japanese involvement in ROK industrialization, it’s worth outlining a good counter-example of ineffective economic aid.

If Ukraine doesn’t have a nearby Japan like the ROK did, don’t they share another common ally – the USA? Well, the USA had very bad luck in developing the ROK. Of course, the USA did have such intentions, since a prosperous ROK would have been a great propaganda victory against the communist world. But until the 1960s (when Japan intervened), the communist DPRK economically developed far more rapidly than the ROK. Between 1953 and 1960, the US provided US$1.6 billion in civilian aid – but much of this was squandered by state-owned companies8. Despite its crucial geopolitical position as a weapon against US enemies, ROK imports in 1962 were 6 times bigger than its exports – the gap was financed by the US through the IMF and WB9.

The total inefficacy of US aid to the ROK is clear from a single statistic – 88% of all US aid (around $4.5 billion USD) to the ROK was received before the Korean growth period of 1966-197710. Because the US insisted that its aid be spent on purchasing US consumer goods, instead of the capital goods which the Koreans wanted, the aid could not be used productively11. From 1954-61, nearly two-thirds of the US aid was used for non-project assistance which financed imports of various raw materials and finished consumer intermediate and investment goods. The remaining one-third was for project assistance and surplus agricultural products12. And every consumer good imported means a corresponding drop in investments for domestic industries that could have produced such goods.

This is similar to modern Ukraine, whose rapidly degrading industry and large trade deficit don’t force the country to default simply because of geopolitically motivated loans from US-controlled financial institutions like the IMF.

The US is not capable – nor willing – to engineer real economic development in its geopolitical ‘frontier states’. It found it more important to market its agricultural, consumer and military goods in the ROK (with negative effects for the ROK economy), just as it finds it more important to sell its weapons to Ukraine instead of assisting the latter in creating a domestic military-industrial complex. And this is quite rational – if the US assisted all its client-states the way that Japan did for the ROK, the USA would rapidly run out of money to subsidize its own society’s consumption.

Japanese involvement in ROK industrialization

Japanese financial assistance

The magnitude of Japanese financial assistance was clear from the start of ROK industrialization. Korea’s first Five-Year Plan (1963-1967) required $200 million, only 30% of which the ROK was able to raise on international capital markets by 1964. Enter the Korean-Japanese Normalization Treaty of 1965 – as a result, Japan committed to $800 million over a 10 year period. Japanese companies agreed to lend $300 million and the Japanese government gave a loan of $200 million – and, remarkably, a grant of $300 million. Such financial generosity has never been seen in the financial relations between the West and Ukraine, for instance.

Simply in terms of savings, the ROK did not have anywhere near enough to make the investments it needed on its own. The following graph shows how foreign savings were more important than domestic savings in the crucial Five-Year Plans (FYP) of the 1960s and 1970s. It also illustrates one of several situations where ROK planned economic targets were much lower than what actually happened – because it was Japanese capital in charge of Korean economic development, not ‘wise Korean elites’.

Japanese financial assistance to the ROK contrasted sharply with that of the US. Where the US did not allow the ROK to use US financial assistance to buy capital goods, Japan encouraged the ROK to do so. Most of the liquidity the ROK received as a result of the Normalization Treaty was used to buy capital goods and industrial raw materials13.

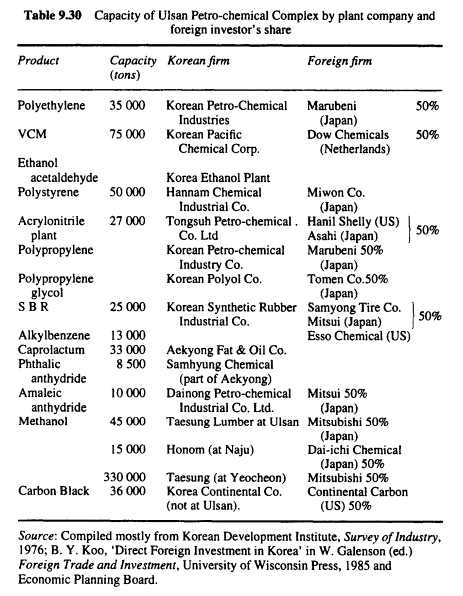

The story of the ROK’s heavy industrial sector is another good illustration of the crucial role of Japanese financing, in contrast to the role of the US14. By the 1970s, the ROK was in a similar position to Japan in the 1960s – wages were rising such that the old export basis of textiles was becoming uncompetitive. The leadership of the ROK acknowledged the necessity of diversifying into heavy industrial sectors such as petroleum, chemicals, iron and steel, electronics in the 1977-79 heavy industrial plan. This way, Korean wages would face less competition from very low-wage nations, which dominated the textiles market.

However, the IMF and the US refused to finance these plans. According to the World Bank, ‘an integrated steel mill in Korea is a premature proposition without economic feasibility’15. Citing the market laws of comparative advantage, the IMF and WB argued that a low-wage country like the ROK needed to specialize in exporting labor-intensive goods like textiles, that investing in a large new heavy industrial complex was dirigiste nonsense which would quickly result in bankruptcy.

Enter Japan, which was only too eager to get rid of its own heavy industrial complex, becoming uncompetitive due to rising Japanese wages. The ROK’s steel industry, which the US, IMF and WB refused to fund, reached its ‘turning-point in the early 1970s when the govemment created Pohang Iron and Steel Company (POSCO) and entered into an agreement with the 'Japan Group' consisting of Nippon Steel and Nippon Kotion Steel’. The POSCO received most of its financial capital from Japan, on 'excellent loan terms from Japanese banks'16.

While the US forbade the ROK to use its loans to buy capital goods, Japan encouraged it to do so. This also means that the official statistics overstate the importance of US credit for ROK industrial growth - where Japanese credit was used to buy the raw materials and machinery needed for industry, US credit could generally only be used to buy finished US consumer goods17. The ROK used its Japanese funds to import 82% of its textile machinery in 1972, with other sectors also highly dependent on Japanese industrial machinery:

Japanese foreign investment

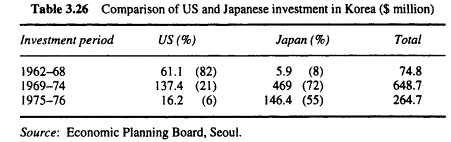

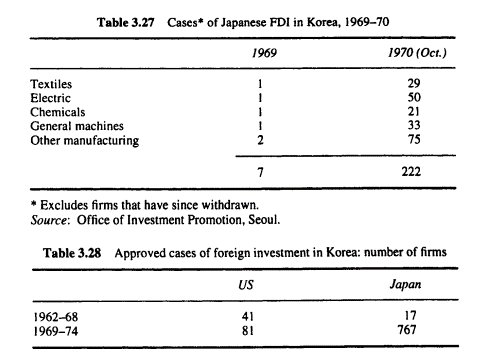

The role of Japanese foreign investment in ROK industrialization also can’t be overstated. In the early 1960s, the ROK faced a problem familiar to poor nations – despite their best efforts to attract foreign investors from Europe and the USA, they were simply unwilling to invest in a country with such a small consumer market and low skill levels. But because of Japanese state policy, that changed dramatically.

Take heavy industry - by 1972 foreign firms accounted for 54 per cent of total production and 72 per cent of exports18. And these foreign investments were often made in the most technologically advanced parts of these industries, the foreign firms thereby giving the less advanced Korean firms access to markets and new technology19.

This took place through direct Japanese state intervention. The textiles industry is a good example. As we have seen, the Japanese government decided in the 1960s that it was not viable for Japan to remain in the textile industry. As a result, it encouraged massive Japanese textiles relocation to the ROK. It did this through state financial assistance to Japanese firms that invested in the ROK (the carrot), and by lowering tariff walls on the Japanese textile sector (the stick)20.

In turn, the ROK textile sector – universally recognized as the key industry which propelled ROK industrialization throughout the 1960s and early 70s – was entirely dominated by Japanese investment.

One of the best proofs of how it was not mainly ROK elite genius that led to its industrialization, regards the relation of ROK economic plans to reality. Instead of the wise Park Chung-Hee guiding the ROK to industrialization and prosperity, it was Japan’s economic interests that determined the course of ROK economic development.

The ROK planned to export $84 million in clothing, but actually exported $304 million. They planned to export $6 million in footwear, but actually exported $37 million. The ROK government didn’t even provide any special measures to support the textile industry until 197721, long after the sector had already meteorically expanded – more proof of how misguided it is to explain ROK economic growth by reference to the wisdom of its political leaders.

ROK political leaders did not have much control over the process – it was the needs of Japanese industry, under pressure by rising domestic wages, which controlled the direction of industrialization in the ROK. As we have already discussed, Japan needed to relocate its textile sector, and hence in the 1960s Korea’s textile sector ‘took off’. Then in the 1970s as Japan’s heavy industrial sector became outdated due to rising wages, it relocated it to the ROK. The ROK didn’t even plan for electrical products to develop in this period (table 5.4b), but reality developed otherwise – because of Japanese interests.

The dependence of the Korean heavy industrial sector on Japanese foreign investment is hard to overstate -

as compared to US investments:

in terms of individual cases of new investments over time, especially in the crucial driving sectors of ROK industry:

and as the main investor in particular mega-projects:

Finally, it should be noted that Castley argues available statistics actually understate the importance of Japanese investments in ROK economic growth. This is because economic statistics on foreign direct investment do not take into account the popular Japanese practices of sub-contracting production, reinvesting funds by overseas subsidiaries of joint ventures, and providing equity shares and loan capital to Korean producers22. In addition, before the 1970s the ROK did not clearly define foreign investment, leading to large discrepancies in data regarding foreign investment in the crucial period of the 1960s, all with the tendency to under-estimate its role23.

Japanese market assistance

One of the most important barriers poor capitalist countries face in their economic development is that of finding market demand for domestic production. The ROK was a low-wage country, meaning that the domestic market offered little stimulus even to the textiles industry. Without export markets, there would have been no ROK industrialization:

Meanwhile, exporting to rich countries with large domestic markets is very difficult without knowledge of foreign consumer requirements, legislation, and market characteristics. This, along with crude protectionism on behalf of the EU, is also why Ukraine has had such little success in exporting to the EU market even after the famous EU association agreement of 2016. Due to the deindustrialization wrought by economic liberalization and the corresponding replacement of Ukrainian producers by Europeans, Ukraine’s exports to the EU only sluggishly rose from 2013-2020, falling from 2014-2017. Occasional spikes in export volumes were due to price fluctuations on raw materials markets (Ukraine’s biggest exports to the EU are iron, vegetable oils and wheat), masking a decline in Ukraine’s industrial exports to the EU. For instance, where Ukraine exported $4.6 billion USD worth of machinery goods to the EU in 2013, it only exported $3.9 billion USD worth of machinery to the EU in 2020.

Without Japan’s assistance, ROK industry would simply not have been able to penetrate the markets of the rich countries, and whatever investments made in the first five -year plans would have found no buyers. Japanese General Trading Companies (GTCs) already had decades of experience selling textile goods in the US. In the 1950s, they had been taught the specificities of the US market due to US geopolitical interests in seeing a prosperous Japan, and in any case boasted over 60 years of experience exporting Japanese textiles across the world. Urged on by MITI, Japanese GTCs taught their Korean junior partners about the various specificities of the US market and gave them the US contacts needed to sell there. This was especially important for consumer goods industries such as textiles, which are highly consumer-driven and do not tolerate producers without knowledge of domestic consumer preferences24.

The immense economies of scale provided by these large-scale Japanese marketing intermediaries was also a crucial factor in ROK export success25. Furthermore, Castley points out how important Japanese marketing and product specification advice was in the 1970s, when Korean business began specializing in heavy industry. This is an even more competitive sector than textiles in which technological and marketing requirements were even more demanding26.

According to Mitsui (a large Japanese company), Japanese trading companies were responsible for marketing half of the ROK’s exports in the 1960s and 1970s27. The Japanese government encouraged this assistance by the GTC through financial aid to companies that invested overseas28, but it was also often in the interest of the GTCs themselves to aid Korean business. For instance, the GTCs wanted to minimize trade risks and hence encouraged Korean export diversification29. GTCs were also able to minimize the effects of fluctuating exchange rates on Korean exports due to their financial sophistication30. Finally, GTCs were known for efficient use of capital and hence gave their Korean partners easy access to credit31.

Japanese technology transfer

Since Japan was attempting to exit the sectors that it was developing in the ROK, and hence faced no threat of economic competition from the ROK, it was very generous in transferring technology and the skills required to use it to the ROK.

In 1974, Japan is estimated to have accounted for 84 per cent of the technology supplied to the Korean electronics industry32. This was in stark contrast to the US, which only gave ‘aid’ loans to the ROK that could be spent on buying US weapons and consumer goods – the opposite of technology transfer.

Korean firms also had access to informal ties with Japanese engineers, consultants, and technicians who came to the ROK on weekends or other holidays and assisted Korean firms in mastering new technology33. They did this as a way to earn extra money, but the linguistic ties between Korea and Japan were a crucial condition of possibility for such assistance. As the economic historian Alistair Amsden wrote, ‘access to such technical assistance placed Korea in an enviable position. Other late industrializing countries further afield from Japan culturally and geographically have lacked such a resource to draw on.’34

As a result of generous Japanese technological assistance, the ROK actually spent quite little on R&D – only 0.8% of GDP compared to Japan’s 2.8% in 1965-198035. But the ROK got its technology from Japan, so there was little need to spend much on R&D. This also encouraged economic growth, since taxes were lower than they would have been without Japanese technological assistance. It is another example of how unwise it is to explain the ROK’s economic development purely with reference to internal factors.

General lessons of ROK industrialization

Hopefully it should be clear to the reader that it is unjustifiable to explain ROK industrialization purely based on wise Korean leadership and policies. The role of Japan was principal. Several lessons can be extracted, whose implications for modern Ukraine we will soon discuss.

First, economic development is not an assured fact for poor nations that possess a ‘wise elite’.

Second, no matter the geopolitical significance of the client-state, the US is not able to simply will economic development into being. Even if it would like its client-state to present a compelling example of economic prosperity, US mercantile interests take priority.

Third, while dependent industrialization for a minority of states is possible, it depends on a constellation of specific factors – cultural-linguistic affinity, and most importantly, objective economic interest. It was in US economic interest to simply sell the ROK US goods and thereby keep it poor – it was in Japanese economic interests to industrialize the ROK.

Can Ukraine count on ‘its own Japan’?

Japan was Korea’s old colonizer, and it was only amidst large Korean opposition that the 1965 Korean-Japanese Normalization Agreement was signed. Ukraine borders on two former colonizers with which it maintains cultural-linguistic affinities and economic links – Russia and Poland. Naturally, the current geopolitical situation removes Russia as a contender for ‘Ukraine’s Japan’. Poland remains, a role which it might seem quite happy to assume, if its president’s recent announcement that soon, ‘there will be no borders between Ukraine and Poland’ are anything to go by36.

However, the comparison between that of Japan in the 1960s and Poland today is quite contestable.

First, the Polish elite hardly seems enthusiastic about developing Ukraine, unlike Japan’s vigorous approach to developing the ROK. Poland has always supported the most liberal elites in Ukrainian society – the first foreign diplomats to come to the Maidan square in 2013 were Polish, and it was the Polish elite that always found time to fly to Kyiv to enthusiastically support the post-2014 elite and Ukraine’s new role as a hyper-liberal avant-garde of ‘the West’ against ‘Russian barbarism’. One can read an article on Foreign Policy titled ‘How Poland Turned Ukraine to the West’.

Compare this to the relationship between the Japanese-ROK elites. Park Chung-Hee admired Japan’s military-statist industrialization, himself having served as an officer in the imperial Japanese army. He worked in the extremely non-liberal ‘State of Manchurio’, a Japanese puppet state whose approach to economic development can be justifiably compared to that of the 1930s USSR.

The fact is that where Japan was interested in industrializing the ROK, Poland is interested in the opposite with Ukraine. The economic motive to Polish interest in Ukraine is quite clear – the deindustrialization caused by its ‘civilizational choice to join the European family’ led to millions of Ukrainians migrating to work in Poland. Poland itself was in desperate need of lower wage workers as Polish wages grew and Polish workers left to the richer countries of Europe. The Polish central bank estimated that 11% of Polish GDP growth from 2014-2019 was due to Ukrainian migrant workers.

Paradoxically, that fact that the Japanese managed to be more racist than the Poles might even mean that Ukraine is worse off than the ROK was. This is because mass Korean migration to Japan wasn’t possible due to extremely restrictive Japanese migration policies, as compared to the many millions of Ukrainians that Poland allows to – and even encourages – to work in Poland. In the words of the Polish Prime Minister Murawetski at the beginning of February 2022, ‘If Russia ends up invading Ukraine, our borders are open… Polish businessmen value Ukrainian workers, and each year we expect to need more of them’.37 Poland doesn’t need to relocate its production to Ukraine, since it can just relocate Ukrainians to Poland. But Japan had to relocate industry to Korea, because they didn’t want too many Koreans polluting its ethnostate.

One of the big factors leading to Japan choosing to relocate production to the ROK were the tariff walls the US put up against Japanese textiles in the early 60s. But the US isn’t likely to put up tariff walls against Poland any time soon. First, because the US is a financial power today which cares much less about export penetration than it did in the 60s vis-a-vis Japan. The US simply has much less industry to worry about losing. It cares about Chinese industrial competition, yes, but Poland is a much smaller country which correspondingly does not present the same threat of wholesale ‘stealing’ the remaining industries of the US and western Europe.

Far from severing economic links with Poland, to counteract the Chinese threat the US is actively trying to ‘reshore’ production away from its geopolitical rivals and towards its allies, especially Poland. But before you get excited that this will happen for Ukraine as well, don’t forget that this is private capital, and private capital won’t be going to Ukraine, a war-torn country which even before the war had far worse infrastructure and skill levels than Poland.

Another factor to consider is that soon European goods will be becoming much less competitive on the world market due to increasing energy prices. Chinese, Indian goods will become correspondingly more competitive, given that they aren’t sanctioning Russian energy resources, and the latter is forced to sell it to them for a 10-30% discount. This would militate against Poland expanding into Ukraine, because it’s possible that Polish enterprises will simply go bankrupt in any case. Castley writes in his book how the oil crisis of the mid-70s quite adversely affected the Korean economy in 1973-74 (Korean exports declined by 7.7% in 1974 because of this38) because Japan stopped being interested in foreign investments as increase in oil prices cut into production costs39.

On other hand, after the initial drop in investment the oil crisis also eventually pushed MITI to conclude that Japan had to specialize in higher tech sectors to avoid being crushed in these more competitive world market conditions, which in turn pushed Japan to relocate its old, more labor-intensive sectors to the ROK40. Where before it might have been possible to compete with lower-wage producers in labor-intensive sectors, with the increase in oil prices it became impossible. Maybe there could be a similar tendency with Poland vis-à-vis what remains of Ukraine.

But it seems to me that the current energy crisis is much longer term and damaging for the EU than the energy crisis of the 70s, since today the EU is trying to totally divest from gas/oil and switch to renewable energy. Total divestment towards ‘green energy’ is far riskier and with questionable long-term viability41. In the 70s there was simply a price increase caused by OPEC, but no attempts at totally cutting off from oil/gas.

Reflections on Ukraine’s place in the world capitalist system

We’ve seen that the comparison of Ukraine to the Republic of Korea has little basis in economic reality. Of course, this doesn’t rule out Ukraine repeating the ROK’s ‘success’ in dictatorial rule based on fear of an external enemy, extermination of trade union and other working class leaders, and institution of barbaric labor legislation42. But what can we say about Ukraine’s place in the global capitalist system?

The global capitalist system is very distinctly divided into high-income nations and low-income nations. In 2020, the high-income nations (earning upwards of $30,000 a year) composed only 11% of the planet’s population43. 84% of the planet’s population live in countries where the average income is less than $10 thousand a year. Only 5% of the planet’s population live in countries where the average income is between $10 thousand and $30 thousand – the ROK and Poland are members of this small group. Many of these countries used to be low-wage nations, and managed to significantly increase wages through exporting to the high-wage nations, almost always on the condition of their geopolitical importance in ‘containing’ threats to the domination of the high-wage nations.

The high-wage nations have always depended on the low-wage nations as a source for cheap imports to offset the effects on profitability resulting from increased domestic wages. Therefore the high-wage nations encourage – or militarily impose – economic liberalization on poor nations, to make sure that wages cannot grow behind protectionist barriers, and that they continue supplying the cheap goods that the rich countries need.

Nevertheless, this demand of the rich nations for exports from the low-wage nations also creates a certain opportunity to industrialize for the low-wage nations. When the circumstances especially fortuitously align – as they did for the ROK in the 1960s – a low-wage nation can even catapult into status of a upper-middle wage nation on the basis of exporting to high-wage nations.

But the demand of the high-wage nations is limited – this is a market economy, where products are only imported when domestic consumers can pay for them. Accordingly, significant economic development through exporting to the rich capitalist nations is a path available only to 5% of the earth’s population. Europe and North America only need a fixed amount of consumer goods. They get more than enough of these goods from Mexico, Poland, coastal China and a handful of other low-wage countries. Lacking foreign investment, most of the poor capitalist world hence remains poor, and this is something that not even the wisest military dictator can change. They are simply unnecessary for the global market. There’s no domestic purchasing power, and the purchasing power of the rich countries is already satisfied.

Those poor countries that do ‘succeed’ in joining the outer edges of the globally parasitic rich countries did not do so because of the wisdom of domestic elites – it happens due to geographic and historical chance, as we have seen in the case of the ROK and Japan. Most of the earth remains poor. Ukraine’s poverty is hardly any absurd deviation from the ‘European norm’, as it is often portrayed inside Ukraine. Ukraine is simply an ordinary ‘third world’ country – like most of the world. To go beyond this structural position, for all but a small minority of ‘Polands’ and ‘ROKs’, means going beyond the limits of the market economy.

Vivek Chibber, Locked in Place: State-Building and Late Industrialization in India, Princeton University Press: 2006. Page 57

Chibber, Locked in Place, page 63. See also his article ‘Reviving the Developmental State? The Myth of the National Bourgeois’ https://escholarship.org/content/qt2bq2753n/qt2bq2753n_noSplash_485e5329a461b62e9ab024ba5b77c62a.pdf?t=krnbo9

Robert Castley, Korea’s Economic Miracle: the Crucial Role of Japan, Macmillan Press Ltd: 1997. Page 353

Kim, K. 8., Korea-Japan Treaty Crisis, Praeger, New York., as cited in Castley, Korea’s Economic Miracle: the Crucial Role of Japan, page 87, note 15

For the following explanation of Japanese motives, see Castley, Korea’s Economic Miracle, ‘Japan’s Relationship With Korea’, pages 78-109

Castley, Korea’s Economic Miracle, page 250

Castley, Korea’s Economic Miracle, page 248

Castley, Korea’s Economic Miracle, page 79

Castley, Korea’s Economic Miracle, page 79

Castley, Korea’s Economic Miracle, page 113

Castley, Korea’s Economic Miracle, page 114

Castley, Korea’s Economic Miracle, page 114

Castley, Korea’s Economic Miracle, page 116

See Castley, Korea’s Economic Miracle, ‘the Heavy Industries’, pages 252-293

As cited by Castley, Korea’s Economic Miracle, page 276

Castley, Korea’s Economic Miracle, pages 277-278

Castley, Korea’s Economic Miracle, pages 124-125

Castley, Korea’s Economic Miracle, page 260

Castley, Korea’s Economic Miracle, page 260

Castley, Korea’s Economic Miracle, page 249

Castley, Korea’s Economic Miracle, page 250

Castley, Korea’s Economic Miracle, page 131

Castley, Korea’s Economic Miracle, pages 316-7, page 333,

Castley, Korea’s Economic Miracle, pages 196-199

Castley, Korea’s Economic Miracle, page 199-200

Castley, Korea’s Economic Miracle, page 204

Castley, Korea’s Economic Miracle, page 245

Castley, Korea’s Economic Miracle, page 201

Castley, Korea’s Economic Miracle, pages 198-9

Castley, Korea’s Economic Miracle, page 199

Castley, Korea’s Economic Miracle, page 200-201

Castley, Korea’s Economic Miracle, page 267

Castley, Korea’s Economic Miracle, page 155

As cited in Castley, Korea’s Economic Miracle, page 155

Castley, Korea’s Economic Miracle, page 165

https://www.unn.com.ua/ru/news/1975577-kordonu-mizh-polscheyu-ta-ukrayinoyu-faktichno-ne-bude-duda

https://www.eurointegration.com.ua/rus/news/2022/02/1/7133371/

Castley, Korea’s Economic Miracle, page 189

Castley, Korea’s Economic Miracle, page 21

Castley, Korea’s Economic Miracle, page 48

https://www.nytimes.com/2022/03/22/business/economy/ukraine-russia-europe-energy.html

https://www.opendemocracy.net/en/odr/ukraine-suspends-labour-law-war-russia/

https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.ADJ.NNTY.PC.CD

I traveled from Tokyo to Seoul in 1967 in the company of a Monsanto plant engineer (he built 'em) and asked how much his company was investing in the factory he was constructing.

"And what return on its investment did Monsanto expect?? I added.

Oh, over 100% annually, he said. We won't go into a project for less than that.

Great analysis.

Interestngly, this is what Russia basically wanted from Yanukovich. Like Park Chung-Hee, he could become that russified illiberal protectionist that would allow Russia to offload the industries that it would grow out of due to rising wages, provide its own domestic market and skills of sending stuff abroad.

In short, the Euromaidan fought against turning Ukraine into a weaker form of RoC under patronage of weaker form of Japan.

What happened instead is that Russia kept these industries to itself due to stagnating wages, as well as importing of cheap central asian labor. Worse for Ukraine, worse for Russia. A big win for liberal democracy.