Portrait of the Joker as a young man: Zelensky 1978-1998

Zelensky's cyber-socialist father. Life in Krivoy Rog. Comedy as corrosive anti-soviet force. The origins of Kvartal 95

If the concept of the State has been described as the great metaphysical abstraction of modernity, then the statesman is an even more mysterious figure.

Gone is the medieval superstition of the king as the all-powerful earthly embodiment of God. Today, the pretense of voluntarism surrounding a political leader gives rise to innumerable suspicions. The subjectivity of any heads of government is automatically doubted. It is much more appealing to speculate about the hidden economic, political, or foreign interests manipulating the puppets in state livery.

There is surely no one shrouded in as many contradictory abstractions as Volodymyr Zelensky. Western puppet, or possessed patriot with as little respect for the White House as the Kremlin? Earnest warrior against corruption, or populist controlled by oligarchs in cahoots with the Kremlin (the latter accusation a favorite of Ukraine’s pro-western nationalists)? Statesman or comic? Beacon of democracy or drug-addicted dictator?

A riddle wrapped in a mystery inside an enigma, as Churchill once said about Russia.

A Joker, as the recent biography of Zelensky recently released by Ukrainian political analyst Konstantin Bondarenko is called. Bondarenko, currently living in Austria, is a ‘polit-technolog’ – that delightful term of the post-soviet space, describing something between a political analyst, consultant or demiurge. Just a few days ago, Bondarenko was officially sanctioned by Zelensky, which the polittechnolog took as a sign of work well done.

Since today’s article is in large part based on Bondarenko’s book (which can be purchased here), I thought I’d begin with a brief extract on our hero’s epochal significance:

Zelensky has become the embodiment of both postmodernity and the rethinking of our role and place in the new geopolitical reality, as well as a leader who had to guide the country through its most difficult times. He is the Joker in the grand political game - the most valuable card that bears the image of a jester yet possesses extraordinary power and weight. At the same time, in contemporary culture, the Joker is an evil clown from comics and later from the Batman series. Isn't it telling that in 2019, just three months after Zelensky's inauguration, Todd Phillips' film "Joker" was released worldwide - a sharp social thriller that in many ways proved prophetic for Zelensky?

….

I don't claim to know the absolute truth. I'm merely presenting my perspective on the processes that have taken place in Ukraine and the world in recent years. As fate would have it, at the center of these events was the protagonist of our story - Volodymyr Zelensky. A talented actor. A statesman with controversial political qualities. The President of Ukraine. A diagnosis of Ukrainian society in the first quarter of the 21st century.

If Zelensky is the symptom, what is the disease?

Zelensky’s discourse is itself so two-dimensional, so sickly sweet in its sincerity, that it is difficult not to dismiss this ridiculous mirage in favor of some hidden interests, both his own and those standing behind him. But notwithstanding the existence of those interests, Zelensky remains a question that must be answered.

In Ukraine, one of the most common discursive motifs, apart from blaming all ills on ‘corruption’, is to bemoan the ‘elites’, inevitably specifying that ‘ours are not true elites’. But in fact, any country has elites – a comprador elite is still that fraction of society with the most power over the country’s resources, even if this elite is essentially a sub-contractor for foreign powers. And furthermore, any elite is to some extent a reflection of that society. While it may not always do what the people wants, it is at any rate forced to appeal that people’s abstract desires.

The rot goes deep, so to speak. Bondarenko points to the startling results a Ukrainian sociologist presented on the eve of war:

These studies yielded unexpected results: the behavioral, cognitive, and perceptual level of Ukrainian society corresponds to that of a 12.5-year-old adolescent! With unformed life principles, where "want" dominates over "should," with rebellion against parental oversight, with no clear understanding of life's path ahead, with tendencies toward paternalism, and with anxieties about independent life. This explains the irrational choices consistently demonstrated by Ukrainians. This also accounts for the regularly staged "festivals of disobedience," like the Maidan protests - ultimately fruitless and futile, yet crucially important for an adolescent's formation of an identity. Hence the widespread obsession with passing trends, superficial worldviews, and casual attitudes toward traditions - for genuine faith and authentic values only come with maturity, which is a prolonged and painstaking process.

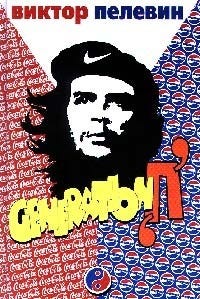

Generation P

Even if Zelensky were merely a PR hologram, the need to create just such an image illustrates something not only about Ukrainian, but post-soviet society as whole.

And Zelensky is certainly not a hologram, since he was a noticeable fixture of Ukrainian and Russian cultural, political and business life for decades before he even thought about the presidency (note that fixing the date when ‘he’ decided on such a path is a question of symptomatic controversy, to be explored in future articles). Reflecting upon his life is hence quite fruitful in understanding these societies.

Separating sincerity from subterfuge is always misguided. Especially so for the post-soviet world, where the most cold-blooded cynicism calmly coexists with fanatical idealism. In this, Zelensky is a perfect cypher for his generation, those born in the 1970s and 1980s. It is this group that dominates activist politics in both Russia and Ukraine, generally setting itself against the ‘stale soviet bureaucracy’.

Since this group dominates political discourse to such an extent, a brief characterization is necessary. These are people born at the economic peak of the Soviet Union, but whose childhood experiences of it were limited to Gorbachev’s destructive reforms, set to the beat of addictive western media content and consumer goods.

With no pre-soviet experience to measure things by, they were sure that the alternative their country had was either present realities or those of the west. And in the west, as everyone knew, the sun was always shining and people were always smiling.

Bondarenko points out that the Ukrainian-American novelist Chuck Palahniuk called this the snowflake generation. The popular Russian novelist Vladimir Pelevin described this generation in a popular 1999 book called ‘Generation P’:

Once upon a time, Russia truly had a carefree young generation that smiled at summer, the sea, and the sun—and chose Pepsi.

Now, it’s hard to say exactly why that happened.

Having matured in the Darwinist capitalism of the 1990s, representatives of this generation disdain the state and find expectations for ‘paternalism’ quaint and deplorable. If they have a political ideology, it is libertarianism. Generally, their radical individualism and disdain for any forms of collectivism makes them markedly antipolitical – Zelensky’s party famously described itself as ‘radical centrists’ in 2021.

Not only are they anti-political, but also anti-historical. Conceptions of responsibility before society or the weight of history are very cumbersome for the snowflake’s individuum. For them, there are no authorities, and hence the only authority is the individual. No wonder such libertarians can easily morph into dictators. Only emotions can be trusted.

Zelensky’s election in 2019 can be seen as the final victory of the snowflake generation over the old guard. His predecessor, Petro Poroshenko, assumed the pose of the radical euro-nationalist, but he has always been a true veteran of Ukraine’s court intrigues and economic squabbles. Zelensky, though he also inhabited that world, did so more as a wandering jester than a player. As we will see in the course of Zelensky’s comedic career, though he constantly gave private shows to both Russia and Ukraine’s heads of states, he clearly had a secret disdain for his audience.

He never took the game seriously, hence Poroshenko’s constant accusations that Zelensky was a populist dilettante that would bring the country to ruin. By the way, I know not a few Ukrainians who voted for Zelensky in 2019 hoping for peace, but now ruefully reflect that the ‘ultranationalist’ Poroshenko might have saved the country from war, precisely because of his cynical experience in navigating post-soviet politics. Perhaps, though that isn’t today’s topic.

Raising a Joker

Zelensky was born in 1978, 78 kilometers from the village where Leon Trotsky was born. Fitting, perhaps, for a man whose presidency would be characterized by such voluntarism and boundless impulsiveness that top Ukrainian businessman Vadym Novinsky called Zelensky and his party ‘new Bolsheviks, but without Marx’. Bondarenko recalls that another Ukrainian writer once told him the following:

Mark my words: Zelensky is Trotsky minus the education. Trotsky represented intellect multiplied by willpower and adventurism. Zelensky is willpower and adventurism with the intellect subtracted.

Zelensky was also born in the same year as Emmanuel Macron. A figure very close to Zelensky, and someone also quite representative of the global ‘Generation P’ in his erraticism, personalism, and shape-shifting nature.

The future president was born in the city of Krivoy Rog (Krivyi Rih in Ukrainian, but I’ll use the Russian spelling for this Russophone city). It is both quite peculiar but also an archetypal soviet city. It is peculiar geographically, often called the longest city on earth (or at least Europe) - over 70 kilometers long, and 5-7 kilometers wide.

This is because it is a city built around iron deposits. It is about as proletarian a city as one can imagine, with its 650,000 inhabitants mainly depending in one way or another on the massive Krivorozhstal steel factory, the largest such factory in Ukraine.

In this sense, Krivoy Rog is an archetypal Soviet industrial city. Such cities are also often called ‘monocities’, because they depend on the economic activities of one ‘city-forming’ factory. In Russia, such cities, like the famous Magnitogorsk, are known as mainstays of support for Putin’s government. They felt the effects of liberal deindustrialization worse than anyone.

Liberals despise such cities as ‘useless, subsidized soviet industry’, and their voters as ‘bydlo’, that term of insult for the working classes which means ‘cattle’, subservient to their autocratic, communist leader. Krivoy Rog is largely Russian speaking, though there is also a current of those from neighbouring villages who speak ‘surzhik’, a mix of Russian with Ukrainian.

It is a city that barely existed as something beyond a mine until Stalin, with a population of 20,000 in the 1920s. It was in large part built by the Soviet industrialization of the 1930s, rising to to 200,000 inhabitants by the eve of the Second World War. When I used to visit the city, I was impressed by all the buildings and locations named after Sergo Orjonikidze, Stalin’s industry tsar, who played a major role in building the city.

The first thing you notice when your train enters city is the reddish haze suffusing everything – iron ore. The city itself is a strange mixture of small houses that wouldn’t be out of place in a rural village, three-storey worker’s residential buildings built in the Stalin period, rusting mines, larger apartment blocks, and the hulking presence of Krivorozhstal. One of the city’s attractions is its strange public transport – it has one of the world’s longest tram lines, stretching alongside the elongated city both above and below ground.

It's an interesting place for a president to come from. A characteristic conversation I remember overhearing from my visit in early 2021 took place in one of the city’s sprawling outdoor markets. I’d made my way through second-hand knockoffs and an array of sturdy shovels to find a sector of outdoors food stalls. I sat down to eat some deep-fried chebureki, a Georgian bread filled with meat. Without much to do, I listened to a man at my table tell his not entirely credulous companion about a youtube video he’d just watched that demonstrated how the government was using covid vaccinations to implant chips into people’s brains.

But Krivoy Rog was always, at very least, close to very important locations. It was in the same oblast as the slightly larger city of Dnepropetrovsk, the so-called ‘workshop of cadres’ I wrote about here. From that city came leader of the USSR Leonid Brezhnev, leader of the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic Vladimir Scherbitsky, head of the Soviet-wide KGB (1982-1988) Viktor Chebrikov, and minister of foreign affairs of the USSR Nikolai Schelokov.

Despite its proximity to the crucial city of Dnepropetrovsk, Krivoy Rog was still its poorer sibling. Where Dnepropetrovsk was a closed city due to its production of ballistic missiles, Krivoy Rog stuck to iron and coal. Salaries were higher than in the countryside, but life was – and is – quite harsh.

In the 1980s, drug addiction and production started blossoming in Krivoy Rog. It was at the avant-garde of this phenomenon both in Ukraine and across the entire Soviet Union. The city also experienced a wave of youth crime, which was also quite characteristic of Soviet industrial cities of the perestroika period. This is from Bondarenko’s book:

In the mid-1980s to early 1990s, Kryvyi Rih was swept by a wave of "runners" - teenagers who formed rival gangs and raided opponents' territories. Over 10 years of gang activity, 28 children and one police officer were killed. More than two thousand teenagers were injured, with medics documenting hundreds of mutilations. Under the laws of that time, preventing such crimes was nearly impossible: children under 16, even caught with weapons or explosives, were difficult to prosecute.

Kryvyi Rih hooligans were nicknamed "runners" due to their combat tactics: teenagers would charge together through rivals' territories, throw homemade grenades, use firearms, and destroy everything in their path - even overturning cars and police vehicles. Runners united into neighborhood-based squads - by district, block, avenue, or boulevard. Other groups had names like "bulls," "horses," "station gang," "cabbage rolls."

By the way, I highly recommend watching the 2023 TV show ‘Word of a Lad’. This Russian series depicts the turbulent lives of members of such gangs in 1980s Kazan, a city in provincial Russia. Notwithstanding nationalist furor, the show and its soundtrack dominated Ukrainian spotify for months. It marvelously depicts the violent emergence of market relations in 1980s Russia, and serves just as well for understanding Ukrainian society. I am told that versions can be found online with English subtitles.

Many of the men who would later become Ukraine’s oligarchs grew out of just such youth street gangs. There is much to be said for the formative effect such groups had on broader society, on Generation P. A lack of moral principles other than personal honor, the need for retribution in response to insult.

In any case, there is no reason to suspect that the young Zelensky had anything to do with such activities. Zelensky, who would become the great hero of the post-soviet ‘creative class’, was born into a typical family of Soviet technical intelligentsia.

All evidence points to the conclusion that Zelensky’s family was highly loyal to the Soviet authorities. Zelensky’s paternal grandfather, Semen Ivanovich Zelensky (1924-1993), fought bravely in the ranks of the Red Army - commander of a mortar platoon and later a company commander in the 174th Regiment of the 57th Guards Rifle Division, part of the 8th Guards Army, itself under the Third Ukrainian Front and later the First Belorussian Front. He received two Orders of the Red Banner and became deputy head of the criminal investigation department of Krivoy Rog after the end of the war. Two of his brothers had died fighting the Wehmacht.

Zelensky’s father, Alexandr Zelensky, was born in 1947. He represented the great technological advances of post-war Soviet society, the hope that new information technologies could perfect economic planning.

Alexandr Zelensky also had quite the impressive list of titles. In 1983, he defended his Candidate of Sciences dissertation on the topic "Automated Calculation of Iron Ore Reserves in a Quarry Management System" in nowhere other than the specialized academic council of the Moscow Mining Institute, specializing in Mine Surveying. Doctor of Technical Sciences, Professor, Head of the Department of Computer Science and Information Technologies at the Krivoy Rog Economic Institute from 1995 onwards.

In 2003, he earned his doctorate at Ukraine’s National Mining University. The topic was once again mine surveying, with his dissertation titled ‘Methodological Foundations of Mine Surveying for Planning and Production Accounting in an Ore Quarry Management Information System’.

In short, Alexandr Zelensky was a fixture of the Soviet industrial economy. Interestingly, in the 1980s and 1990s Zelensky senior often collaborated with Nikolai Azarov, who was then head of the Ukrainian State Research and Design Institute of Mining Geology, Geomechanics, and Mine Surveying in the Donbass city of Donetsk. Azarov would become prime minister under Yanukovych and was hated by Ukrainian liberals and nationalists for his social democratic, even socialist views.

Azarov is highly active in Russian talk shows to this day, and there are plenty of rumours that he may make a return to Ukrainian politics, if Russia manages to neuter Ukraine’s nationalist right. While I don’t know how possible that is, it is quite strange to contemplate Azarov, the scientific and industrial colleague of Zelensky’s father, coming back to face off with the son.

Zelensky’s father must have been a model soviet citizen. Such a conclusion can be reached based on the fact that he was able to travel abroad – he lived and worked in Mongolia for twenty years. This was notable, since the KGB was highly – and rightfully – suspicious of intellectuals of Jewish descent for their western and Zionist sympathies. In contrast to many of his colleagues, Alexandr Zelensky remained steadfast in his loyalties –his son, the hero of our story, received a grant for free study in Israel when he was 16, but his father refused to let him go.

In Mongolia, the older Zelensky also set about perfecting socialism. At the Erdenet Mining and Processing Plant, in the computer department of the copper-molybdenum complex, he co-founded Mongolia’s first school of cybernetics and computer technology alongside his Mongolian colleague Burenbayar.

He also enjoyed close ties with the Soviet deep state. According to Bondarenko, Alexandr Zelensky became close friends with Sergei Nechaev, the Second Secretary of the General Consulate of the USSR in Erdenet. Then responsible for the unofficial surveillance of all Soviet citizens and their families stationed in Mongolia, he is today the Russian Federation’s ambassador to Germany.

Those who remember Alexandr Zelensky speak highly of him. Nowadays, just about every Ukrainian university has a well-oiled system of bribery to get top marks in exams – Dr Zelensky apparently never accepted such money.

Bondarenko relates an interesting story of father-son relations in the Zelensky family. The future president, at this point a wealthy comedian, gave his academic father a car on his birthday. However, Dr Zelensky turned it down. While he thanks his son, he pointed out he could afford the present one his own salary.

However, I’ve found other statements by Zelensky’s father. In 2021, Zelensky made the fateful decision to sanction a number of TV channels in Ukraine that criticized him and pro-NATO militarism. As I’ve written, this has been widely interpreted as a major reason for Putin’s decision to go to war - pro-Russian, or at the very least non-aligned sentiment was now banned in Ukraine, and Russia could not hope to influence Ukraine through allied political parties.

Zelensky father supported the decision when asked about it by strana.ua. Amusingly, he also admitted that until some months back, he too had watched these ‘pro-Russian’ channels. But he complained that they criticized his son far too much.

“Maybe I don't understand democracy... Well, I don't like it. It's not like I have any influence over it. I mind my own business. Sometimes it's all presented so crudely on TV, well, it's just not right."

He declined to comment on how this would affect freedom of speech in the country. In the same interview, he flew into a profane rage when asked about rumors that he and his wife had left Ukraine amidst the rumors of imminent Russian invasion:

What 'going abroad' are you talking about? I live and work here! Why would we leave? That's all nonsense. We'd rather die for Ukraine. All around they're just spouting rubbish - they'd be better off grabbing a shovel and going to the trenches to defend Ukraine. Apparently those who write about this have nothing fucking better to do!

In any case, the era of Dr Zelensky was over with the end of the Soviet Union. With post-soviet deindustrialization and the fragmentation of Union-wide production chains, men like Alexandr Zelensky would be less and less necessary. Graduates of information technology found work in transnational cybercrime instead of solving the problems of socialist planning. The new era needed showmen rather than leaders of industry.

Corrosive comedy

The young Vladimir (I use his Russian name, since he was entirely Russian-speaking until 2019) Zelensky was by all accounts an exemplary student. Though he spent four years in Mongolia in the 80s, most of his life was in Krivoy Rog. He studied in school number 95 – the city is divided up into ‘quarters’, or kvartals, and he lived in the 95th quarter. Here he studied English in an experimental class where English had to be spoken even at break times. It was in high school that he met his future wife, Elena.

Nicknamed ‘Green’ (his surname contains the word) and Hummer’, the young Vladimir kept abreast of western trends. In this he was not alone among his cohort. Besides the usual sports and musical activities that befitted a soviet school student, he also wore an earring and was interested in rock music, playing guitar in the school band.

All accounts agree that Zelensky was a star student. Here’s what the Ukrainian publication strana.ua found out in 2019 when they asked his former teacher at school no 95:

He was very active, involved in school life and in all events. In the 6th grade, he won the “Gentlemen Show” competition among 12 schools in Kryvyi Rih. In the 10th grade, we staged a theatrical performance of Gogol’s The Marriage. Vova played a supporting role, but he did it so brilliantly that everyone remembered him. Sometimes you watch professional actors on TV, trained in this craft... But no one taught Vova. He did it all himself. A naturally artistic, talented boy,” recalls Valentina Ignatenko, Deputy Principal for Educational Work at Gymnasium No. 95.

….

“Zelensky had a very deep voice from childhood. Such a small boy – such a grown-up bass. And at first, when he was heard in the choir, they said – Vovochka, maybe it’s better if you don’t sing. But you see, he matured. He came to the music room during every break. He was persistent. If he wanted something, he always achieved it,” recalls one of Zelensky’s teachers. Zelensky himself once admitted that as a child he was self-conscious about his voice. But one day he realized that it wasn’t a flaw, but a memorable feature. And from that moment on, no school celebration went by without his signature raspy bass.

Who among the young Vovochka’s teachers at school no. 95 in Krivoy Rog’s ‘Soc-City’ suburb could have guessed that in forty years’ time, this very voice would be beamed into the televisions of the whole Free World, relentlessly demanding more weapons, money, and weapons…

In fact, they might have had an inkling. At school, Zelensky dreamed of becoming a diplomat, and wanted to study at the ultra-prestigious Moscow State Institute of International Relations. While he quickly realized such a prospect was out of his reach, he still studied law at a university in Krivoy Rog. Though his education proved unnecessary for his future, Zelensky’s professor in constitutional law recalls that his peers chose Zelensky as president of Ukraine in simulated elections that the professor organized in 1996.

How did this exemplary young Soviet citizen transition into the new age of freewheeling capitalism?

Vovochka didn’t socialize through the street gangs, as his school never had him on the list of known hooligans. Nor did the young Zelensky ever get the chance to enter the Komsomol, being as he turned of age just as the Soviet Union was imploding. It was in this communist youth organization that the Soviet Union’s first legal small businesses emerged in the 1980s. Many of Russia and Ukraine’s most well-known oligarchs and politicians started their career in the Komsomol – Yuliya Tymoshenko and Viktor Medvedchuk are two Ukrainian examples.

In the 1980s and early 1990s other youths of his age in the gangs and the komsomol earned fortunes at breakneck speeds – or died trying. But Zelensky was socialized from a young age in another network – comedy.

The ‘Club of the Happy and Inventive’ (KVN) was created in Nikita Khruschev’s 1960s ‘thaw’ in relation to western culture. It was banned in 1972 as an ideologically foreign phenomenon, but revived again under Gorbachev’s perestroika in 1986.

Gene Sharp was years away from releasing his 1993 manual on how to defeat ‘authoritarian regimes’ through non-violent actions, chief tactic among which he named comedy and various comedic performances. Such tactics would be used widely in the 2000s post-soviet space. But comedy also played a role in the dissolution of socialism in the 1980s.

The KVN included standup, sketch humor, and revue theatre. All this was structured by teams of comedy groups that competed against each other. It seems that they found anti-soviet humor sold well – or, just as likely, they were instructed to do so by the pro-market fractions of the KGB and politburo that curated various ‘dissident’ cultural phenomena. The following is from Bondarenko’s Joker:

On July 18, 1988, just two weeks after the conclusion in Moscow of the extraordinarily important 19th Party Conference of the CPSU, a significant moment occurred: the KVN team from Novosibirsk uttered a bold phrase during one of their performances:

“Party, let us take the wheel!”

This was a direct challenge to the entire Soviet system—after all, Article 6 of the USSR Constitution defined the Communist Party as the leading and guiding force of Soviet society. And this phrase could be interpreted as the youth encroaching on the constitutional order!

Historians believe that this very phrase— which sparked roaring laughter across the Soviet population—marked the beginning of the gradual collapse of the Communist monopoly on power: the CPSU was no longer seen by the public as a frightening and rigid monster.

What dissidents and politicians had failed to do, the young comedians of KVN accomplished:

The system stopped being feared.

The system became a joke.

In the 11th grade, the young Zelensky organized a team of student comedians at school no.95 to play against a team of teachers in the KVN format. The students won. Many of those that Zelensky organized his first KVN team with would continue along Zelensky’s side throughout his future career in show business, and some even continue their careers in the Ukrainian government. It was in honour of school no.95 in kvartal 95 that Zelensky’s comedy empire would be called just that – Kvartal 95.

But Kvartal was years away. For now, Zelensky rose up the ranks of the KVN arena. As a student, he was a member of the professional KVN team ‘Zaporozhye – Krivoy Rog – Transit’. Here he met the Shefir brothers, who played such an important role in Zelensky’s career, and continue to be important figures in political life. Here’s how Sergey Shefir described Zelensky in a 2019 interview:

“Vova is like a meteor,” says Sergei. “Speed in everything—movement, thought, humor. A perpetual motion machine. My role with him is to be the string that keeps him tethered; without it, he’d float away like a balloon, high into the sky. He constantly needs to be reined in. He’s the kind of person who doesn’t see obstacles—always charging forward. Incredibly driven. Talent plus relentless work ethic. That’s his formula for success.”

While Shefir interpreted this tendency towards acceleration positively, Bondarenko noted its risks:

Remember these words to understand Shefir’s role in Zelensky’s inner circle after 2019—and why someone might have wanted to push Shefir away from Zelensky.

Those who know Zelensky in real life note his choleric temperament, which borders on capriciousness, along with his extreme demanding nature, perfectionism, and nitpicking tendencies. Many couldn’t handle his hard-edged leadership style. Exceptionally hardworking himself, he expected no less from others. A tough negotiator. Persistent to the point of obsession. He knows how to take risks and has a penchant for reckless ventures. His deadly sarcasm can disarm an opponent. At the same time, his lack of deep education is compensated by sheer assertiveness, often crossing into brash rudeness.

In 1997, the KVN had its 11th premier league since 1986. Twelve teams were invited – three from Ukraine, one from Georgia, one from Armenia, and six from Russia:

· Siberian Monks (Krasnoyarsk)

· Cowboys of the Polytechnic (Kiev)

· Kharkov Cops (Kharkov)

· Plekhanov & Company (Moscow) – finalists of the First League

· Service Entrance (Kursk) – finalists of the First League

· NSU (Novosibirsk) – second lineup of the NSU team

· Vladikavkaz Rescuers (Vladikavkaz) – champions of the First League

· Samara Plane (Samara) – second season in the Major League

· Ural Dumplings (Yekaterinburg) – third season in the Major League

· Real Toastmasters (Tbilisi) – fourth season in the Major League

· Zaporozhye – Krivoy Rog – Transit (Zaporozhye – Krivoy Rog) – third season in the Major League

· New Armenians (Yerevan) – second season in the Major League

Zelensky’s team won. Though this KVN team split up that same year, a new one formed from its remnants that same year. Led by the Shefir brothers, it was comprised of a core of Krivoy Rog comedians from Zelensky’s school no. 95. Hence, it was called Kvartal 95. It made its debut in the Russian black sea city of Sochi in 1998.

Although Kvartal 95 participated in several KVN leagues throughout 1998-2003, it was never able to win the premier league again. It won several Ukrainian leagues of KVN, but it was doomed to disappointment in the finals and semi-finals of the premier league. Kvartal encountered other frustrations as well, as one comedian in the group told Bondarenko:

When we wanted to parody the Russian president, we were told: 'Better joke about your own.' At that time, the president was Leonid Danilovych Kuchma, and our parodies of him were quite successful—strong monologues and sketches. We saw that we had a knack for political satire." However, in Russia, political parody of Putin was only permitted to a select few Russian actors. The Ukrainian team was not among the "approved parodists”.

Instead of vying for success in KVN, Kvartal 95, or just Kvartal as it is often called, would evolve into a fixture of Ukraine’s political and cultural life. And its satirization of Ukrainian politics proceeded apace with the fragmentation of that same polity into rival clans. These clans, engaged in a Hobbesian war of all against war, constantly employed the services of Kvartal both as a weapon against their enemies, and to boost their own political popularity. And Zelensky would personally entertain not only Ukrainian presidents, but also their Russian counterparts. All that and more will be treated in season II of this series. Bring your popcorn.

For now, let’s end with a vintage clip of Zelensky at the 1998 KVN league, complaining about the rigged Russian competition and praising his colleagues from Donetsk:

So, what I want to say is... I'm really happy that our young team from Krivoy Rog made it to the gala concert. But first, I was asked to share my impressions of last year’s Sochi festival and how it differs from this one.

Last year, I came here as a young actor with the KVN team Zaporozhia-Krivoy Rog Transit—it was actually my first trip like this. I had a small comedic role, and honestly, I was completely blown away by the festival. Back then, there were about 200 teams, now even more. It’s all very fun and exciting.

One thing I noticed last year—and it repeated this year—is that young teams are treated much worse than the older ones. But if you really think about it, the level of the veteran teams last year was, in my opinion, way higher than this year’s. That said, I really liked the young teams.

First, I want to say how happy I am that the Donetsk team finally made it to where they’ve deserved to be for so long. I’m genuinely happy for them, and I hope they’ll compete in the Premier League and take the position they’re worthy of.

Now, about Transit… Well, the final was… let’s say, rigged. Everything was on our side, though we honestly didn’t expect a tie. Everyone knew the Armenians would win. The only thing we wanted was to win over the audience.

Every day, during each performance, they cut one of our musical numbers. Masyakov (the KVN host) removed them. We had this genius metal screen—weighed like 80 kilos, maybe more—and it was just a ridiculous quick-change gag, a really interesting musical bit, about a minute and a half long. They axed it.

In the end, in the broadcast version, they cut seven jokes—all the transitions and musical numbers. What you saw on TV was just six jokes in the introduction and two blocks in the homework (EIU - pre-performed segment).

In the live show, we didn’t expect such success with the musical parts—we won by a huge margin. We thought it’d be more even. But before the final round, we thought, ‘No way it’s this clean… Are we really about to beat the Armenians?’

And then the homework… I personally think it was Transit’s strongest performance ever. The jury deliberated for 40 minutes—couldn’t agree. Then Masyakov asked them not to raise the scores for the final round for some reason, and in the end, they forced a tie.

So now, I guess we just wait… Either for the Super Cup or a rematch—though we don’t really want to play again.

Perhaps Zelensky still feels bitter about the KVN victory snatched away by the cruel Russian judges?

Thanks for the freebie.

cool article did not know about him in Mongolia or his dad being invloved in soviet economic planning